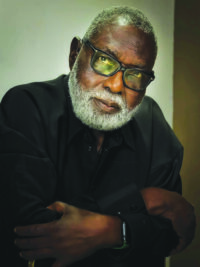

Leading volunteers demands a broader range of skills, a deeper understanding of human behavior, and a more deliberate approach to influence, argues LINUS OKORIE

There’s a certain assumption that leading people is more or less the same, regardless of the context. As long as you have a clear vision, communicate well, and hold people accountable, they’ll follow. But anyone who has ever led a group of volunteers knows that this assumption collapses quickly.

When you manage staff, there is structure. There are contracts, job descriptions, salaries, and performance reviews. There are consequences for failing to show up, for missing deadlines, for underdelivering. These formalities provide an invisible net that holds the entire system together.

With volunteers, that net does not exist. They show up not because they have to, but because they want to. That difference, subtle on the surface, is the single biggest challenge and, paradoxically, the greatest opportunity in leadership. However, the truth that many hesitate to admit is that leading volunteers is more challenging. It demands a broader range of skills, a deeper understanding of human behavior, and a more deliberate approach to influence.

Let’s look at why. First, motivation looks completely different when there is no paycheck involved. In a traditional workplace, even the least engaged employee has a reason to stay, which is their livelihood. You can count on that baseline. With volunteers, there is no such bottom line. Their reasons for joining vary wildly: personal passion, social connection, a sense of duty, a desire to be useful, even boredom. That means leaders cannot rely on compensation to motivate; they must lean entirely on purpose.

Purpose, though, is slippery. It has to be cultivated, communicated, and continually reinforced. You cannot just tell someone that their contribution matters; you have to show them. That might mean connecting their tasks to a larger mission or sharing stories that spotlight the impact of their work. It requires leaders to become meaning makers, not just task managers.

Second, the usual authority structures that help managers lead employees do not exist with volunteers. When you manage staff, you have institutional authority. There are rules, policies, chains of command. But volunteers do not report to you in a legal or contractual sense. They owe you nothing. You have no power over them except what they choose to give you. That shifts the leadership dynamic dramatically.

To lead volunteers, you have to earn influence every day. That means showing up with empathy, clarity, and trustworthiness. It means being the kind of leader people want to follow, not because they have to, but because they choose to. It is not about pulling rank; it is about modeling consistency, compassion, and conviction.

Diana ran a volunteer-led community food bank in Texas for over ten years. When asked how she kept dozens of volunteers coming back week after week, she talked about sending handwritten thank you notes to her volunteers, celebrating their birthdays, and weekly check-ins where she asked volunteers how they were doing outside of their food bank duties. “People show up where they feel seen,” she said simply. That is leadership by influence, not authority. And these are the limitations of performance reviews or management software.

A third challenge lies in retention. While staff turnover is disruptive in any setting, volunteer turnover can be devastating. A volunteer walking away can mean the collapse of a crucial program or the loss of institutional memory. But because there is no contractual commitment, volunteers can and do leave without notice. Leaders must therefore cultivate not just enthusiasm at the outset, but deep-rooted loyalty.

And loyalty, unlike enthusiasm, is built over time. It is built in the slow moments when leaders listen, appreciate, include, and elevate their people. It is built by creating a culture where volunteers feel that their presence is not just welcomed, but essential. This emotional glue is often more powerful than any job title or HR policy. Yet building it takes effort, intentionality, and patience.

Then there is the complexity of managing expectations. Employees are hired into clearly defined roles. They know what is expected of them, what success looks like, and who they report to. Volunteers rarely receive this kind of clarity. They often come into environments with unclear roles, inconsistent communication, and widely varying levels of commitment.

This means volunteer leaders have to do more upfront work to align expectations. They must communicate roles with precision, be honest about what the work entails, and remain flexible as volunteer needs and circumstances change. It is an ongoing dance of clarity and compassion; being structured without being rigid, and being kind without being vague.

Finally, there is the issue of training. New employees usually go through some form of onboarding, orientation, or probation period. Volunteers, however, are often thrust into action with little more than a verbal briefing. That puts pressure on leaders to provide quick, clear, and empowering guidance, especially when volunteers are working with vulnerable populations or mission critical tasks.

When there is no time for extensive training, leaders must master the art of simple instruction and fast trust building. They must communicate with clarity, model behavior, and delegate in a way that inspires confidence, not confusion. Mistakes made by volunteers are not just operational glitches; they can be deeply discouraging and can lead to dropout. Volunteer leaders have to coach on the go and build systems that support learning by doing, without letting people feel like they are failing.

All of this paints a clear picture that leading volunteers is not easier because it lacks the formality of staff management. It is harder because it is more human. It strips leadership of its scaffolding and leaves only the bones of influence, integrity, and interpersonal skill.

That is not a weakness; it is a gift. Because in leading volunteers, you are forced to lead from the inside out. You have to draw on emotional intelligence, storytelling, empathy, and service. You cannot shortcut your way through systems or hide behind hierarchy. And when it works, it is some of the most beautiful leadership you will ever witness.

So, what does effective volunteer leadership look like in practice?

It looks like consistent communication. People cannot stay engaged with a cause if they rarely hear from those leading it. It looks like meaningful recognition. This means offering more than a generic thank you and instead giving appreciation that is personal and sincere. It looks like clarity of vision. Volunteers need to understand how their individual contributions connect to a larger purpose. It looks like flexibility. Leaders must remember that volunteers have full lives with jobs, families, and other responsibilities. And most of all, it looks like care. This is not just about caring for the mission, but about showing genuine concern and respect for the people who make that mission possible.

When you get it right, something incredible happens. Volunteers do not just show up; they bring their whole selves. They become advocates, mentors, fundraisers, even future staff. They breathe life into your mission in ways no payroll could ever capture.

But you have to earn it. Every day.

That is why leading volunteers is not just harder than managing staff, it is also, in many ways, more rewarding. Because when someone gives you their time freely, and you steward that gift with excellence, you are not just leading. You are inspiring. And that, in the end, is what true leadership is all about.

Okorie MFR is a leadership development expert spanning 30 years in the research, teaching and coaching of leadership in Africa and across the world. He is the CEO of the GOTNI Leadership Centre.

Leave a comment