Jess Castellote

A few days ago, I stumbled across an essay by a Japanese writer I had never heard of before—Junichiro Tanizaki. Written in 1933, its title was In Praise of Shadows. Despite its age and the vanished world it describes, Tanizaki’s reflections on shadow and dimness felt surprisingly current. With quiet elegance and a very poetic tone, he meditates on the beauty of shadows, on the richness of dim spaces, and on how traditional Japanese aesthetics embrace what we moderns, with our obsession with light, often miss. His words stayed with me. They made me reflect on how we view art today—how we almost instinctively prioritize clarity, colour, and brightness. Museums, galleries, and even coffee table art books place a premium on illumination. Our visual language is built on the assumption that to see is to see light. But Tanizaki suggests we may have lost something in that pursuit. What if shadow, far from being a lack, is a presence in its own right? What if we have forgotten how to see shadow?

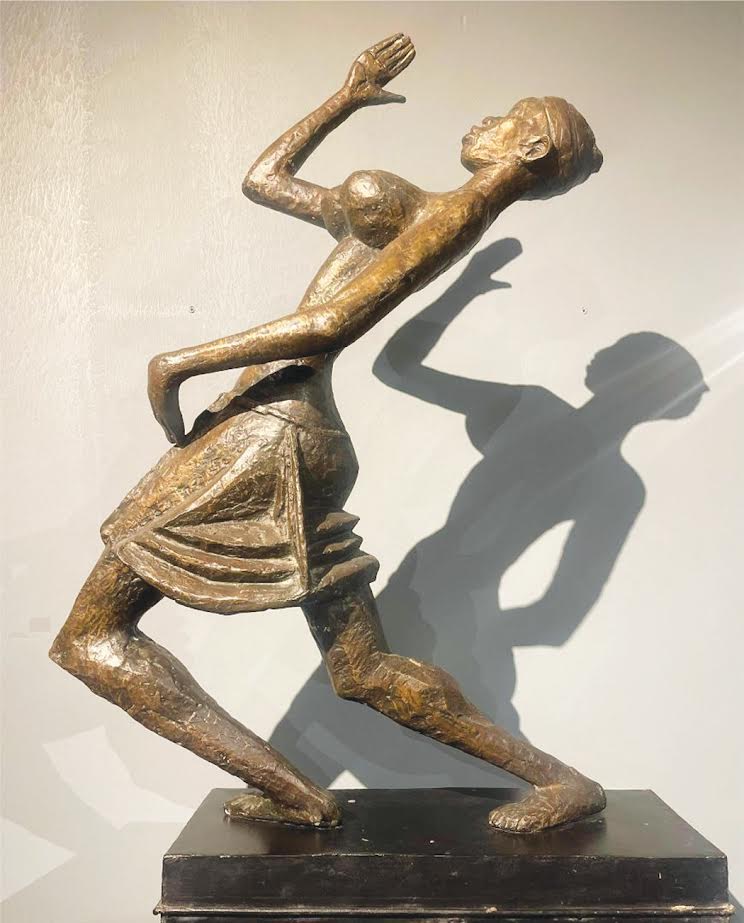

Shadow is more than the absence of light. It is presence. It carries its own beauty — subtle, evocative, and often more complex than light itself. Light reveals, shadow suggests. Brightness declares, shadow whispers. When we first installed works from our permanent collection at the Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, we selected a striking bronze sculpture by Ben Enwonwu titled ‘Africa Dances.’ It is a work that pulses with motion: limbs extended, head lifted, the energy of the dance captured forever in metal. Rather than follow the common convention to position it in the centre of a room—lit from all sides, detached, floating—we placed it near a wall with a single, powerful beam of light. The result was spectacular. A second sculpture, one made purely of shadow, emerged on the wall behind it. Elongated, sinuous, trembling with suggestion, this shadow figure became as expressive as the bronze itself. A dialogue emerged between viewer and sculpture, but also between matter and absence, between the tangible and the implied. This wasn’t accidental — it was an act of faith in shadow.

The American architect Louis Kahn once remarked, “The sun never knew how great it was until it fell on the wall of a building.” His point was about transformation, about how light gains form and character through encounter. But the same can be said for shadow: it becomes compositional when it falls on a surface, stretching, shifting, and gaining shape. Perhaps “a shadow never knew how wonderful it was until it fell on a receptive surface.” At that moment, shadow becomes more than absence; it gains direction, shape, and character. That’s exactly what happens with the shadow of Africa Dances at YSMA. Cast onto the museum wall, it becomes a presence in its own right, a gesture made in silence and darkness.

I’ve come to think of shadow in two distinct ways, though we often use the same word for both. There’s the shadow—singular and defined—like the one cast by Enwonwu’s sculpture. It’s not just an afterthought but a presence that dances alongside the bronze itself. When that single beam catches the sculpture, the shadow it throws becomes a companion to the work, extending the dance into dimensions the solid form alone cannot reach. I find myself watching visitors’ eyes move from bronze to shadow and back again, witnessing their discovery that the artwork exists in this conversation between substance and projection.

But then there’s the other kind—shadows, plural, overlapping and gentle. This is the quality Tanizaki wrote about, the soft dimness that fills a traditional Japanese room or the quiet corners of our more contemplative gallery spaces. Here, no single shadow announces itself; instead, layers of gentle darkness build upon each other, creating depth rather than contrast. In these spaces, visitors lower their voices instinctively and slow their pace. The artwork doesn’t reveal itself all at once in such lighting. It unfolds gradually, offering different aspects as the eye adjusts and discovers. Both experiences—the bold, singular shadow and the gentle wash of shadows—have their place in how we encounter art. One declares while the other suggests; one performs while the other envelops.

At YSMA, we’ve embraced this. Our gallery walls are painted a quiet, balanced grey, not cold or clinical, not too warm or distracting. This subtle tone sits between light and dark, reducing glare and allowing artworks to breathe. Rather than overwhelming the eye, the space encourages a slower kind of looking. Shadows have room to move and become co-creators. The shadow of Africa Dances is not an incidental effect, it is part of the experience. The wall does not merely display the sculpture; it receives and reflects it. The gallery becomes a space not for spectacle but for seeing.

Shadow is the sculptor of volume. In our flat, glowing digital age, where screens eliminate depth, shadow restores dimension. Without it, the world would be eerily smooth. A face would lose its contours, a fold of cloth its weight, a tree its mystery. Painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt built their entire visual language around shadow. They painted darkness into which light entered, not the other way around. Photography, too, is a medium of shadow. From its earliest days, photographers learned that darkness was not emptiness but a compositional tool defining mood, structure, and intimacy. In architecture, shadow gives a building its soul. In sculpture, it makes form tactile. Without shadow, the visible loses its richness. Shadow sculpts, anchors, and deepens.

There is a serenity to dimness, especially in interior spaces. Rooms lit not by uniform brightness but by restrained, directional light invite a different kind of attention. They awaken a slower kind of looking, a more reflective presence. In such places, we pause more. We notice details. Not all shadow is the same. Like light, it carries tone. Afternoon shadows glow with ochre; moonlight shadows slip into blue. Indoors, the effect depends on the source: candlelight makes shadows dance, while fluorescent light renders them harsh. Artists understand this deeply. Shadows are not black; they are purples, blues, dusty browns. Painters instinctively reach for these tones to evoke mood and time.

Perhaps museums are among the last places where shadow is still taken seriously. In a culture obsessed with visibility and exposure, museums offer spaces where the unseen is allowed to remain partially hidden, where things can whisper instead of shout. At YSMA, we talk often about “quiet drama”, not theatricality, but the slow unfolding of attention. Visitors don’t always notice at first. But over time, many say they feel more immersed, more connected. We avoid drowning the galleries in uniform brightness. Instead, we allow artworks to emerge slowly from shadow, into focus, and back again. Visitors often linger longer in our dimmer rooms. It is not darkness we offer, but a kind of deliberate restraint, an invitation to dwell.

This sensitivity to dimness extends beyond museums to domestic settings—especially bedrooms, reading corners, or living rooms—where low light has always created comfort and intimacy. I am a strong advocate of warm light in homes. Light like the golden hue of late afternoon or the gentle glow of incandescent bulbs bathes everything in subtle warmth, softening edges and deepening colour. A standing lamp, a shaded bulb, the flicker of a candle, these don’t just illuminate; they shape atmosphere. We often overlook this when we pursue brightness at all costs. Offices and stores now glow with the cold, blue-white light of fluorescent tubes and LED panels that flatten the world, erasing shadow, texture, and tone.

In Nigeria we know well the familiar silence that follows a power outage. In those moments, we reach for torches or mobile phones, whatever light we can find. The room shifts. Light becomes softer, more focused. Shadows stretch and flicker. The world takes on a different texture, more intimate, more human. A single point of light in a dim room transforms the space, creating room for quiet presence. In that half-light, faces soften, voices lower. The edges of things become less defined—but more evocative.

To praise shadows is not to scorn light, but to understand that vision is born from contrast. A room without shadow can feel flat, like a sentence without pauses. Life without shadow would be without subtlety, without rhythm. In a time so saturated with visibility, there is a kind of resistance in shadows, and complexity in embracing it. There is dignity in gentle dimness that allows details to emerge slowly. This kind of shadow is not oppressive but generous. In it, textures speak louder than colours. Forms appear more tactile. Dimness slows us down. Our gaze becomes less analytical, more contemplative.

So, the next time you walk into a gallery, a museum, or your own living room, pause. Let your eyes adjust. Look at the tone—warm or cold—of the light in the room. Notice how light reveals, but how shadow completes. Look at the penumbra, the silhouettes, the shifting greys. Let yourself enter that soft world behind the visible. There, in the quiet, in the half-light, you might find not only new dimensions of the object, but new ways of seeing it.

•Dr. Castellote is the Director, Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art. Pan-Atlantic University

Leave a comment