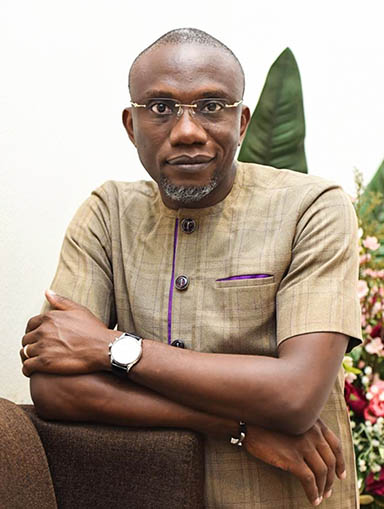

Renowned political economist and public intellectual, Prof. Pat Utomi, reflects on his upbringing, the state of Nigeria with piercing honesty and clarity. He opens up about the formative influences that shaped his work ethics and worldview, his disillusionment with Nigeria’s political elite, and his persistent commitment to systems-driven leadership rooted in creating value over amassing wealth. Sunday Ehigiator brings the excerpts:

Can you share insights into your early life and upbringing?

I had a very pan-Nigerian upbringing, which is why the depth of ethnic divisions in Nigeria today deeply saddens me. I was born in Kaduna on February 6, 1956, the same day Queen Elizabeth II visited. My mother went into labour while trying to catch a glimpse of the Queen, and I was born before she could make it to the hospital. It’s a story I’ve shared with King Charles on two occasions during his visits to Nigeria. I was baptised a few weeks later at St. Teresa’s Catholic Church in Jos. My father, who worked with a British petroleum company, was frequently transferred, so I spent my early years in several northern towns, Maiduguri, Kano, and Gusau, and attended St. Thomas’ Primary School in Kano. Later, I moved to Onitsha for secondary school at Christ the King College (CKC), and when the civil war broke out, I moved to Loyola College in Ibadan. I eventually completed my university education at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, before heading to the U.S. for graduate studies. My upbringing was deeply influenced by Catholicism. I was an altar boy at five and a sacristan by eight. I’d ride my bicycle at dawn to Our Lady of Fatima Church in Nguru to prepare for morning Mass, then return home only to be driven back for school. As a youth corp member, I served at New Breed magazine, a transformative experience. At just 21, I wrote articles that sparked national debate and even contributed to a ministerial reshuffle during the Radio Kaduna-NTA integration controversy. That experience gave me early national exposure and a sense of civic duty. Originally, I wanted to be a pilot; it was the dream job back then. Many of my peers, like Mick Mattas, pursued aviation. But my father persuaded me to try university first, “just to mature a bit.” At Nsukka, I discovered the library and eventually volunteered to help run it, which turned me into a voracious reader and changed the course of my life. Instead of flight school, I went straight to graduate school in the U.S., finishing two master’s degrees and a PhD in just four and a half years. The very day I completed NYSC, I boarded a flight to America. And the day I submitted my PhD thesis, I returned to Nigeria, eager to contribute to national development.

What does a typical day in your life look like, and how significant is spirituality in your daily routine?

My days have followed a fairly predictable rhythm for decades, although I’m now intentionally shifting gears as I prepare for retirement. I typically wake up at 5:00 a.m. and attend Mass by 6:30 a.m., a routine I’ve maintained since childhood.

Faith has always been central to my life. It’s not just a belief system; it anchors me and reminds me daily that my actions must align with my values. I believe faith must be active, not just intellectual. After Mass, I usually head straight to my desk, where I’ve worked for over 30 years, and plan my day. Whether it’s academic work at Lagos Business School (LBS), activities with the Centre for Values in Leadership (CVL), or consulting projects, I allocate time accordingly.

If I’m teaching, I go to LBS and return by afternoon for meetings or more desk work, usually wrapping up around 5:30 or 6:00 p.m. Despite numerous invitations to events, I’ve never been a night person. In earlier years, I might stop briefly at a few evening functions, but I always aimed to be home before 8:00 p.m. Evenings are for family time, dinner, and conversations, after which I retreat to my study until around 1:00 a.m. Faith continues to be a guiding force. During Mass, I reflect on where I’ve fallen short and recommit to living a life of purpose and impact. That reflection fuels my daily actions. I’m often misunderstood by those who measure success by wealth. But I’ve always believed that true wealth lies in the impact one has on others.

A friend, Ben Murray-Bruce, once joked that I hate money because so many people have become wealthy standing on my shoulders, while I still live simply. In response, I wrote a book titled ‘Business Angel as a Missionary’, reflecting on the businesses I helped build and the people I’ve empowered.

Interestingly, living this way has brought unexpected blessings. In recent years, especially when my political stances attracted backlash, friends from across West Africa, whom I’ve known since the days of the West African Enterprise Network, offered me homes in places like Ghana, Freetown, and Banjul, just so I could escape Nigeria’s tensions. Some even go as far as buying my flight tickets when I travel.

So, I can’t help but be grateful. The life of service and impact has not only brought me fulfillment but, in many ways, has also returned material rewards I never sought.

Looking back at your upbringing, who would you say had the greatest influence on you?

There were many. Naturally, my parents played a major role. My father had an intense work ethic; just watching him made it impossible not to value hard work.

That discipline stayed with me throughout life. When I was in graduate school, my thesis advisor once told a colleague of mine, Fulu Ogundimu, that I was a “pathological workaholic and compulsive overachiever”, not as a compliment, but a critique. Still, that mindset helped me complete two master’s degrees and a PhD in just four and a half years. My mother was also incredibly hardworking, but more nurturing. Beyond my family, the Dominican priests at Our Lady of Fatima in Nguru shaped me profoundly. Fathers like Fr. Fama and Fr. Makati, and reverend brothers like Brother Eugene and Brother Louis Mary, were pillars in my early formation.

As I got older, other mentors influenced me deeply: Dr. Christopher Kolade, Dr. Pius Okibo (Nigeria’s first Chief Economic Adviser), and Ukpabi Asika, former Administrator of the old Eastern Region. In my book, ‘To Serve Is To Live,’ I reflect on how their values impacted my own.

Academically, I was drawn to the School of Institutional Economics. Scholars like Douglas North and my head of department at Indiana University, Eleanor Lindstrom, had a lasting impact. Lindstrom and I often disagreed during my PhD years, but her brilliance shaped my thinking later on. She eventually became the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economics; her plaque now hangs right outside the room where I defended my thesis in 1982. I recently returned to Indiana University and was amazed at how the environment had improved; a stark contrast to many Nigerian institutions that have sadly deteriorated. So yes, my journey has been shaped by many, from my family to religious mentors, professional figures, and world-class academics. Each played a part in shaping who I’ve become.

What was the defining moment that made you venture into politics?

The person who deserves the most credit for nudging me into politics is Papa Ayo Adebanjo. I had the privilege of engaging with many elder statesmen early in life. For some reason, I was always drawn to older, wiser individuals, and they in turn took an interest in me. A classmate once remarked that most of my close friends were at least 30 to 40 years older than I. But I saw these interactions as opportunities to learn. I would ask them a single question and sit back as they essentially dictated a book to me with their responses. I first became an activist as a 17-year-old undergraduate at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. One defining moment was on my 18th birthday, February 6, 1974. At the time, students across Nigerian universities were protesting in memory of Kunle Adepeju, a student killed by police during a demonstration in Ibadan. Nsukka had remained quiet, as most students were still recovering academically from the Civil War. But a few of us, under the banner of the Student Democratic Society, led by the late Bassey Eyo Bassey, organised a protest. That morning, we marched through campus despite resistance from other students. During a rally later that day, a well-known student activist, Chaman Pinnick, gave a rousing speech, declaring that the post-war student body had finally become mentally demobilised. As the crowd erupted in applause, I suddenly remembered, it was my birthday. I had been so consumed by the movement; I forgot I had turned 18 that day. My activism continued well beyond my university days. During the “Ali Must Go” protests against Education Minister Dr. Ali, I had already graduated and was serving as a youth corps member.

My apartment in Barikisu Iyede Street, Lagos, became the organising point for the National Union of Nigerian Students. From there, we coordinated meetings and even consulted with the late Gani Fawehinmi, whose chambers were nearby. Gani became very fond of me, and my involvement in national student activism deepened.

Years later, Papa Adebanjo told me, “Activists alone don’t change nations. They raise awareness, yes, but real change requires political engagement. You must enter politics.” That was the turning point. His words planted the seed. It wasn’t immediate, but the conviction grew over time, and eventually, I made the leap from activism to active politics.

You later contested to be President of Nigeria. What was the experience like for you, and what were your lessons?

Running for president in 2007 was one of the most intense and defining experiences of my life. Unlike many candidates who get on the ballot just to make a statement, I ran a full campaign, visiting all 36 states of the federation despite having no major financial backers. A few close friends offered their cars, and we travelled largely by road, often in challenging conditions. It was grueling, but it also reaffirmed my deep commitment to Nigeria. One moment that has stayed with me occurred in Gombe, during a courtesy visit to the Emir. I expected the usual formalities and polite words, but what I received was an emotional and unexpected endorsement. He said, “I want to thank you for your decision to run for president. I’m not saying you won’t win, but if by any chance you don’t, please don’t give up. Because until someone like you becomes president, Nigeria will not make progress.” It was both humbling and sobering. He went on to describe how the wrong people often rise to power and surround themselves with technocrats whose advice they routinely ignore. That encounter left a lasting impression on me. At another stop in Adamawa, then-Governor Boni Haruna, a PDP member, lent us SUVs from his official fleet after seeing our struggling vehicles. That act of generosity, across party lines, reflected the Nigeria we once had, where decency and respect for opposing views were still possible. Despite the warm reception in many places, the 2007 election was far from free or fair. The level of manipulation and rigging was overwhelming. Even Umaru Yar’Adua, who emerged as president, openly acknowledged the flaws in the electoral process. It was disheartening. I had hoped our campaign could at least shift the conversation and lay the groundwork for credible, issues-based politics. Instead, I was faced with a system that had no intention of reforming itself.

After the election, Chief Anthony Enahoro reached out to me, urging me to help form a new progressive political movement. But I was deeply discouraged. I had just come through a traumatic political experience, and I felt like I was being punished for trying to do what was right. It’s not widely known how much people like me have suffered; economically, socially, and professionally, because of our principled political stances.

Businesses linked to us are often targeted. We face blacklisting and silent persecution. But we endure in silence, hoping the country will someday understand the price of integrity. Today, we see Peter Obi facing similar challenges, being warned not to enter certain states, having his businesses undermined, and being barred from speaking at universities at the last minute. I’ve experienced those things too.

They rarely make the news, but they are part of the hidden cost of challenging the status quo in Nigeria. The biggest lesson I took from 2007 is that Nigeria, unfortunately, is not a true democracy. What we have is a captured state, where power is hoarded and manipulated, and even the institutions meant to safeguard democracy, like the judiciary and the legislature, are compromised. It’s a dangerous place for a country to be, especially when the political class has become dependent on state resources rather than generating real economic value.

That realisation made me pivot. I decided that, rather than continue in a broken political system, I would focus on what I could do through education, thought leadership, and entrepreneurship. At Lagos Business School, I championed the need to shift attention from corporate managers to entrepreneurs who could drive job creation and economic growth. My advocacy led to the founding of the Enterprise Development Centre (EDC), and I taught the first courses in entrepreneurship there for about a decade. But I didn’t stop at teaching. I actively supported many of my students, standing as guarantor for loans, investing in startups, and sitting on their boards. Some succeeded; a few failed. One former student defaulted on a loan of N11 million, and because of that, I haven’t been able to operate a Nigerian bank account this year. I couldn’t even buy petrol recently because none of my cards worked. That’s the price I’ve paid, putting my money and reputation where my mouth is.

Yet, despite the frustrations, I remain grateful. I’ve learned, I’ve contributed, and I’ve stayed true to my values. Whether through politics, education, or enterprise development, my aim has always been the same: to help Nigeria rise above its challenges and live up to its potential.

Let’s talk a bit about political economy. As a political economist yourself, how do you make sense of Nigeria’s political-economic contradictions today?

It’s deeply distressing. A friend of mine, James Robinson, co-author of ‘Why Nations Fail’ and a recent Nobel laureate, said in a CNN interview that most countries now know what to do to develop, but some, like Nigeria, simply don’t do it. That hit home. Our problem isn’t a lack of knowledge; it’s the selfishness of the political class. They know what needs to be done, but refuse to act. As we speak, 75 per cent of rural Nigerians live in chronic poverty. That’s not just an economic failure; it’s a ticking time bomb for social unrest. In 1960, rural Nigerians were better off. They exported cocoa, palm oil, groundnuts and saved money. Today, they are barely surviving. The system has failed them. The banks that once relied on rural savings now have nothing to draw from. We’ve turned producers into beggars.

Other countries like Vietnam have shown what’s possible: land reforms, agricultural support, and value chain development. Nigeria could be earning far more from agriculture than from crude oil. But our leaders are too self-absorbed to do what’s right.

Is that what inspired your idea of a ‘shadow government’?

Exactly! For democracy to work, there must be people outside power who are still thinking and proposing solutions. That’s what I hoped to build: a credible, intellectual and policy-driven alternative that could critique government decisions constructively. In fact, in 2008, President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua invited me to join his cabinet. I told him I had just formed a policy team that would monitor and advise from the outside, a shadow government of sorts. We argued for two hours at the Villa about whether one can make more impact from within or outside the system.

I told him I would offer advice anytime, day or night, free of charge. But he insisted that being inside would allow me to do more. He asked me to help him identify seven good people for key ministries and add myself as the eighth.

Eventually, I agreed. I returned to Lagos, assembled a list of names, and sent it through the then-Secretary to the Government, Steve Oronsaye. I never heard back. Yar’Adua died not long after. Years later, someone in his inner circle told me he probably never even saw the list. It might have been intercepted.

And regarding the matter with the DSS?

We’re in court. It’s a broader issue of civil liberties and the right to speak truth to power. We’ll see it through.

What exactly do you mean by a shadow government, especially in light of this new coalition?

I’m hoping we all recognise that this must be bigger than individual ambition. It can’t be about “me, myself, and I.” It has to be about Nigeria, about systems, about institutions, not personalities. Otherwise, we’ll keep repeating the same cycle.

Leadership must be collegial, not centralised around one figure. When we place our hopes in a single person —“Oh, Buhari will save us,” or “Oh, Tinubu will fix everything”, we’re doomed the moment they take a wrong turn. Collective leadership creates checks, balances, and resilience. I’ve made these points repeatedly during meetings with members of the coalition. Political parties have been part of Nigeria’s problem. So if we must have one, it must be ideologically grounded.

It must have a strict ethical code, clear values, and a deep connection to everyday Nigerians. The people must see that it serves their interests. If that isn’t the direction we’re heading, I’ll walk away. And I’ve told them that plainly.

Some people in the coalition are being criticised as part of Nigeria’s problem. As someone with a long-standing commitment to reform, how do you reconcile that?

That’s a valid concern, and I understand the scepticism. But let me share a story that shaped my view. In the 1970s, the dominant academic lens for understanding development was ‘Dependency Theory’. Its leading voice was Brazilian intellectual Henrique Cardoso. I once challenged him at a conference, saying the theory was elegant but offered no real solutions. He didn’t answer then. Decades later, I met him again here in Lagos, and we reflected on how much had changed. Cardoso had gone from academic to exile, and then returned to Brazil as Foreign Minister.

One day, he was unexpectedly announced as Finance Minister, even before he agreed to it! On his flight back from New York to Brasilia, he decided to accept, despite the role contradicting everything he’d written. He assembled Brazil’s brightest economists, told them to argue out a real plan, and whatever consensus they reached, even if it contradicted his life’s work, he would back it. They chose globalisation, the opposite of what he had preached. He backed it. Inflation plummeted. Brazil rebounded. He was then asked to run for president, and he won twice. His shift paved the way for Lula and transformational programs like Bolsa Família, which even inspired our APC roadmap years later.

So I don’t judge people by their past alone. What matters is; are they willing to acknowledge past errors and commit to a new path? If so, let’s work together. If they remain stuck in the past, then I won’t walk with them.

One key concern raised by critics is leadership. In your opinion, how should the coalition select a flag bearer for the 2027 elections?

I believe the process should throw up the best person for where Nigeria needs to go, not just the most popular or loudest voice. We need someone with the right vision and credibility. And I do hope the coalition is working toward that.

Do you see yourself playing a direct role, especially considering your history with ADC?

Yes, I feel a strong sense of history here. I was the very first presidential candidate of the ADC. I helped found the party. My commitment to public service predates nearly everyone in politics today; I was serving in presidential advisory roles as far back as 1983. I carry a burden of history, and I intend to let that guide my participation in this process. But let me be clear: if it ever feels like things are going in the wrong direction, I will not hesitate to walk away. And this time, if I walk away, whatever I walk away from will sink.

Let’s talk about the current administration. What is your assessment of President Bola Tinubu’s government over the past two years?

Well, let me start with a caveat: I’ve been living outside Nigeria for about two years now, so I don’t have daily, on-the-ground contact with the situation. That said, I still follow developments closely, and what I see is a troubling mix.

There are some decent actions, but overall, the statistics are unwholesome, and the level of profligacy, especially in the face of widespread suffering, is deeply upsetting. You see, while millions of Nigerians are struggling, the government continues to spend lavishly on jets, yachts, extravagant cars, and luxurious housing for officials. It’s a scandal. I remember that during Obasanjo’s military regime, when oil prices dropped slightly, he immediately banned the use of vehicles beyond Peugeot 504 for government officials. That was leadership with restraint. What we see now is excess, justified as entitlement. And for leaders to defend such spending, at a time like this, is, in my view, unforgivable. Now, I know many of the people in power personally. Bola Tinubu was the Governor of Lagos when I offered significant support, intellectually and morally, in every way I could. I never asked for anything in return, not even a gift. I did it out of a sense of civic duty.

But because they know me, they also know this: I will never compromise my principles just because I know someone. If I see something wrong, I’ll say it, publicly or privately. For me, it’s about conscience and accountability. When I stand before my Maker, I want to be able to say I stood for what I believed was right. That’s what drives me.

What would you say is the biggest leadership deficit in Nigeria today?

At its core, leadership is about being other-centred, thinking about others, not yourself. But what we see today is the exact opposite. Too many so-called leaders are consumed by me, me, and me. What we often mistake for leadership is simply narcissism on display, self-love masquerading as public service.

True leadership also requires humility, the ability to admit you don’t know everything, and the willingness to learn from others. Unfortunately, many of our leaders behave as though they know it all, when in reality, they are dangerously uninformed. They’re celebrated as geniuses, but often it’s just noise, empty barrels making the loudest sound. Another critical deficit is the lack of accountability. Public office is not private property. When citizens demand stewardship, and leaders treat it as an attack, we have a crisis. Accountability is not optional in a democracy; it’s foundational. Lastly, incivility has become a major threat to our public space. Dialogue has degenerated into abuse and propaganda. People fear speaking out because disagreement is often met with insults rather than reasoned debate.

As Jürgen Habermas, the German philosopher, once said, democracy should foster rational conversation and a marketplace of ideas. But here, alternative views are treated as hostile. That drives away many good people. It’s only a few of us, perhaps mad enough, who still speak out, despite knowing we’ll be met with orchestrated attacks from those who often don’t even understand what we’re saying. That’s the tragedy of Nigeria’s leadership climate today.

The recent passing of former President Muhammadu Buhari has generated a wide range of reactions. What is your assessment of his legacy, especially given your interactions with him?

As with all human beings, people will have different opinions about him. But I had significant personal interactions with him. One of the privileges of my life is that I’ve spent substantial time, beyond just greetings, with nearly every Nigerian leader of the past 30 years, except General Abacha. To be honest, I was once very opposed to Buhari, especially during his first term in power. I was among those who didn’t want to see him return. But my views began to soften around 1997 after attending a World Bank and Oil meeting in Hong Kong. There, I met Indonesia’s former oil minister, Prof. Mohammad Sadli, who spoke very fondly of Buhari, recalling him as a disciplined, ascetic Nigerian lieutenant colonel and Minister of Petroleum. That positive impression from an outsider made me re-evaluate my stance.

Later, when Chief Anthony Enahoro passed away, and the progressive political movement was forming what eventually became today’s SDP, Chief Olu Falae told me point-blank: “Buhari has a loyal following in the North, while we recognise his limitations, his influence is essential if we hope to rescue Nigeria.”

Chief Falae even proposed a Buhari-Pat Utomi ticket; his vision being that Buhari would focus on his strength, ‘fighting corruption’, while I would run the economy and give direction to governance.

So, I started engaging more closely with Buhari. We had several meetings, both in groups and privately. I was even with him on the night he received the call that President Yar’Adua had passed away.

But you later pulled back from him. Why?

Yes, I did. My goodwill towards Buhari changed drastically after the 2011 elections. At the time, there was post-election violence in the North, and many believed he could have helped douse the tension. A British diplomat, Peter Carter, who was Deputy High Commissioner in Abuja, told me how hard they tried to persuade Buhari to make a calming statement. But he refused. That disturbed me.

When Bola Tinubu later called to suggest we go and meet Buhari again, I refused. I told him I had seen enough and didn’t think Buhari would cooperate. I even suggested that if Buhari wanted to help, he should nominate someone else, someone like Usman Bugaje, with a broader vision. Tinubu initially seemed open to the idea, but nothing came of it.

But you eventually offered some support?

Yes. I kept my word. I said I’d support the APC effort, and I did; initially. But once Buhari became president and started making those early economic policy statements, many of them abroad, I knew the country was in trouble. I warned Tinubu: ‘This man is going to ruin Nigeria.’ From that point, I began to withdraw. Throughout his eight years, I stayed away. Not out of bitterness, but out of principle. I had seen the signs and didn’t want to be part of it. I wasn’t surprised by how his government turned out.

So, on a personal level, how would you describe him?

He was surprisingly pleasant and humorous in private. People often don’t realise that. He could tell jokes and hold thoughtful conversations. But as a leader, he was deeply lacking in the qualities Nigeria needed at the time. And that’s what matters most.

You’re approaching 70. Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently, politically or professionally?

I often say that if I had to do it all over again, I would probably do everything differently. Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20. But the principles would remain the same. I had the exposure, the talent, and the grace of God to become extremely wealthy early in life, probably even before some of today’s billionaires. Aliko Dangote and I were friends long before he became “Dangote.” I had connections globally: investment bankers, financiers, institutions. If I had chosen to focus on personal wealth, I would have made billions decades ago. But I chose to be a teacher. I chose to build people rather than chase money. When I left the industry to return to academia, many people thought I was crazy. “Who gives up a top job to become a teacher?” they asked. Bamangar Tukur even called me to ask if I was mentally okay. I’ve never hated money; I teach entrepreneurship after all, but I had a healthy contempt for those ruled by money. So I didn’t pay much attention to amassing wealth. Still, I’ve lived comfortably. I’ve travelled the world, flown first class, stayed in the best hotels, all on other people’s budgets.

If there’s one thing you would love to be remembered for, what would it be?

One word: consistency. People, including those on the opposing side of politics, have said this to me countless times. When Mr. Gaius Obaseki was GMD of NNPC, he once said, “Your consistency is unmatched in Nigeria. Everyone knows where you stand.” That means something to me. For 50 years, through ups and downs, I’ve stayed the course. Others who tried to remain independent often gave up, but I kept going, driven by principles. I just wish the Nigerian elite would realise it’s in their best interest to build a functioning country. Why keep fighting each other for scraps when we can all thrive in a working system? It’s baffling. If anything shocks me about Tinubu’s presidency, it’s that I thought he would be even more pragmatic than Yar’Adua. At least Yar’Adua reached out across the divide. I hoped Tinubu would engage in nation-building, but instead, I see division, tribalism, and short-sightedness. That, for me, is deeply disappointing.

Leave a comment