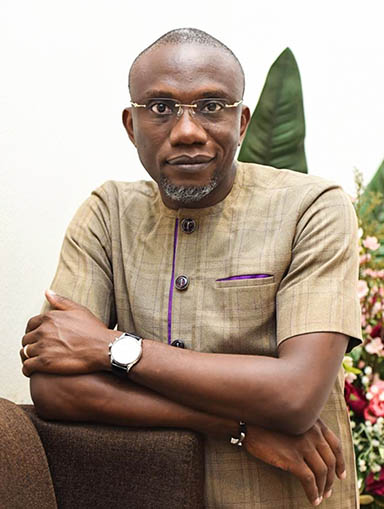

Femi Akintunde-Johnson

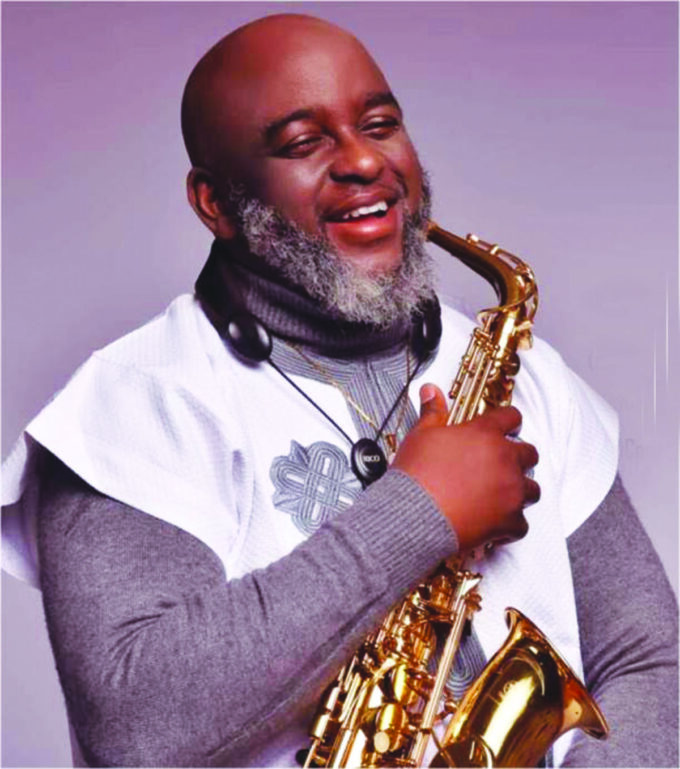

He didn’t just live – he happened. Like thunder on a silent night. Like a stubborn virus in a system built on silence and fear. Fela Anikulapo Kuti was not merely an entertainer, he was a living provocation. From his self-christened name (‘Anikulapo’, the one who holds death in his pouch) to the lyrical shrapnel in his music, Fela dared death long before it came calling in August 1997. And when it did, it didn’t conquer him – it merely gave him a final standing ovation.

Twenty-eight years later, we are still grappling with the enormity of what we lost, and the haunting fact that we didn’t deserve him. Yes, we clapped when he sang, we danced to the fire of his sax, we giggled at his yabis, and hissed at his mockery of our revered hypocrisies. But when he needed a following, a critical mass to elevate his gospel beyond Kalakuta, we hid. Behind pulpits, behind uniforms, behind poverty, and the cowardice of careerism.

Let’s not deceive ourselves: Fela was no saint. He didn’t pretend to be, and he had a long, open disdain for those who weaponised religion to control the docile and deepen societal neurosis. His flamboyance, his rituals, his bold use of substances, his polygamous Kalakuta commune – all of it scandalised the colonial hangover in us. Yet, behind the smokescreen of rebellion was a man on a mission, a man who screamed when others whispered, who stood tall when others crouched behind holy books and military decrees.

Fela’s music wasn’t just a genre – it was a theatre of protest, an audio newspaper chronicling the darkness in high places. From Obasanjo to Gowon, Idi Amin to Mobutu, the mighty were not spared. He had the rare nerve to call a spade not just a spade, but a shovel of shame. In a continent where sycophancy is currency and courage is punishment, Fela chose exile within his own country. And he paid for it – beaten, jailed, stripped, battered. But never broken.

It is the height of irony that the same Nigeria which hounded Fela to the edge of life, became a stage of theatrical mourning the day he died. The lying-in-state at Tafawa Balewa Square was like a national confessional – mourners, media, ministers and misfits all scrambling to rewrite history with sobs and press releases. Even the government, that same notorious entity whose agents had torched his home and tormented his being, seized the moment for international optics. The hypocrisy was suffocating.

And the people? The so-called masses? They wept. Oh, how they wept. But they had already failed him. Fela wanted more than applause – he wanted revolution, reform, resistance. He wanted the people to stop genuflecting before oppressors and pastors alike. He wanted the musician not to merely entertain, but to educate. But our musicians misunderstood the assignment. They thought Afrobeat was all basslines and congas – forgetting that inside those rhythms were blood, satire, and resistance.

He even rejected the tokenism of industry awards. The Nigerian Music Awards, in all their self-congratulatory pomp, tried to hand him an Afrobeat category plaque – as if you give the inventor of fire a plastic lighter. He rebuffed them, unapologetically. And rightly so. Because Fela didn’t need validation from institutions built on mimicry and mediocrity. He was already the template, the benchmark, the bar none.

Unlike Makeba or Masekela who protested from foreign comfort, Fela fought from within. He didn’t need asylum; Kalakuta was his resistance camp. For 25 relentless years, he confronted military regimes, spiritual opportunists, and the middle-class hypocrisy that baptised cowardice as wisdom. His art, his life, even his death was rebellion on full volume.

Yet, what have we done with his legacy? Did we carry his torch or bury it beneath the noise of commercial jingles and vanity lyrics? Did we internalise his message or distort it into a cult of eccentricity? Today, we sample his beats, remix his classics, and wear his face on T-shirts. But how many have the audacity to wear his conscience?

Fela’s death was not a full stop – it was an ellipsis. A continuation. His children, both biological and ideological, have tried in various degrees to keep the spirit alive. But it is not enough to play his vinyls or parade his statue at Allen Avenue (is that still there?). The true homage to Fela is to confront what he confronted: impunity, ignorance, inequality.

His prophecy still stings: sorrow, tears and blood remain our regular trademark. The very ills he screamed about – official thievery, ritualised religion, suffering and smiling – still choke our national airspace. And the people? Still docile. Still worshipping at the altars of those who loot them in daylight and bless them at night.

If there’s anything more tragic than Fela’s death, it is our continued failure to hear him, truly hear him. Not just the beat, not just the melody, but the message: “Teacher no teach me nonsense.” We keep repeating classes we should have long graduated from. Our leaders keep looting, our pastors and imams keep cashing out, and our people keep hoping – on empty stomachs.

But in spite of us, Fela lives. In every chant for justice, in every lone voice calling out hypocrisy, in every saxophone that bleeds truth, he echoes. Not just in the Shrine, or in the October Afrobeat playlists, but in every street corner where resistance stirs quietly like smoke before fire.

Fela was here. A prophet with a horn. A soldier without uniform. A teacher without a classroom. He didn’t just make music – he made meaning. He didn’t just sing truth – he sang danger. And for that, he will never die.

So, light up the sax, not the weed; raise your voice, not just your cup. For as long as Africa still groans, as long as justice still limps, and power still mocks the powerless, Fela Anikulapo Kuti will remain a haunting, vital, necessary presence.

He was here. And we? We are still trying to catch up.

“…My people self dey fear too much

We fear for the thing we no see

We fear for the air around us

We fear to fight for freedom

We fear to fight for liberty

We fear to fight for justice

We fear to fight for happiness

We always get reason to fear

We no wan die

We no wan wound

We no wan quench

We no wan go

I get one child

Mama dey for house

Papa dey for house…”.

(“Sorrow, Tears, and Blood” – 1977).

Leave a comment