Jess Castellote

I ’ve been reading Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman, a great book that has made me reflect on the role of craftsmanship in the arts. Sennett writes with rare clarity about something often overlooked in our competitive art world: the value of doing something well—not for recognition or reward, but simply for its own sake. He calls this “the craftsman’s spirit”—the quiet drive to make things carefully, attentively, and with pride. The more I read it, the more I saw how much this spirit matters in the visual arts, where form, feeling, meaning, material, and execution are inseparably bound.

Art is often judged by its speed of impact or strength of concept. We tend to admire bold ideas, fast results, and clever disruptions. Yet in this rush to be original, artists risk losing touch with something older and more enduring: the commitment to work done well—patiently, carefully, and with respect for process and material. Craftsmanship, in this sense, is not nostalgia. It is a standard. It reminds us that execution matters, that a good idea deserves to be well made, and that material intelligence is central to artistic expression. We have learned to celebrate the concept while quietly neglecting the craft, and we are in danger of forgetting that it is the very foundation of artistic expression.

Sennett defines craftsmanship as the desire to do something well for its own sake. It’s a deceptively simple idea—easily overlooked, yet deeply radical. True craftsperson-artists do not rush toward completion; they live in the process. They find meaning not only in the finished object, but in the hours spent adjusting a contour, rebalancing a composition, refining a line until it sits just right. This challenges the romantic image of the artist inspired by sudden flashes of inspiration. For the serious artist, progress often comes not in leaps but in quiet increments. The artist with this concern for quality works through resistance—of the medium, the idea, and her own limitations. This iterative, physical, intelligent engagement gives craftsmanship in the arts its particular character. Sennett calls it “the intelligent hand”—a form of knowing that arises from doing, not theorizing. It is not mindless repetition. It is immersion.

In today’s art world, an emphasis on concept and personal expression often overshadows technical discipline and material understanding. It is increasingly common for artists to generate compelling ideas yet struggle to give them convincing form. The gap is not in imagination, but in craft. We have all seen it: an ambitious painting with weak brushwork; a sculpture with exciting materials but poor structure; an installation that collapses under its own weight. These are not failures of vision—they are failures of execution. Too often, artists are urged to prioritise meaning and originality before they’ve gained control over line, colour, surface, materials, space, or weight.

Craftsmanship in visual art isn’t about perfection—it’s about conviction and a concern for quality. Without this, even strong ideas risk dissolving into vagueness. And this is so because craftsmanship goes beyond technical skill. It involves imaginative attention: a painter’s sensitivity to how brushes carry paint; a sculptor’s awareness of weight and grain; a photographer’s patience with light; a textile artist’s care with tension and texture. These choices, often invisible, reflect not just ability, but ethics: a willingness to respect the medium, to honour the viewer, and to strive for integrity in execution. This is what separates hurried execution from the careful attention to detail of an artist who honours her craft. She doesn’t settle for just getting the job done; she insists that surface, structure, and presence all reflect deeper care. A functional painting can convey a message. But a crafted one holds more—it embodies time, presence, care, intention.

The sculptor who slowly adjusts each curve in dialogue with the material knows that time is not an obstacle but a companion. Each touch carries weight. Each step affects the next. Shortcuts taken early may save time, but they always show in the end. The quality of an artwork often begins well before it meets the viewer’s gaze. A properly stretched canvas creates a responsive surface. A wood sculpture, well-finished and grain-respecting, invites the hand as much as the eye. In bronze casting, technical precision allows subtle textures to survive the shift from clay to metal. These may seem like backstage concerns, but they are foundational: applying gesso patiently, mounting a photograph so it lies flat, choosing the right paper so ink won’t bleed. Such care reveals deep respect—for the work, the material, and the future viewer.

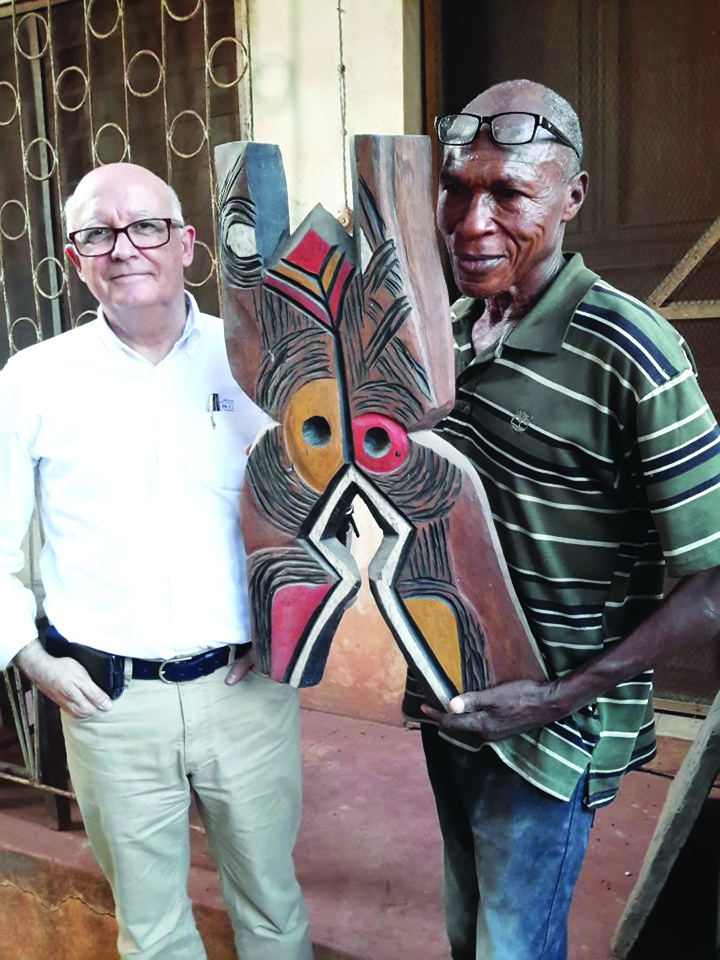

A key part of craftsmanship in the visual arts is what Richard Sennett calls “material consciousness”—a cultivated awareness of how materials behave and speak. The experienced artist doesn’t impose form on inert matter but works with it as a collaborator. The material “pushes back,” Sennett writes, offering resistance, surprises, even guidance. This is a tactile conversation, physical and intuitive. I have seen this vividly in the work of Nigerian sculptor Chris Afuba, who often speaks of “listening to the materials” and allowing them to speak their own language. In his studio, iron is shaped with strength, wood with gentleness. His sculptures—composed frequently of bent rods and carved forms—feel both improvised and precise, as if responding to inner rhythms. This is what it means to work with materials, not just through them. Material consciousness turns technique into judgment. It is the difference between handling clay and understanding it; between using colour and knowing how pigments absorb or reflect light over time. This is a form of intelligence developed only through doing, failing, and refining over many years. Sennett understands well what that “material consciousness” means.

A clay pot or a handwoven textile, if made with this kind of careful craftsmanship, can carry as much emotional weight as a conceptual installation. These objects do not need theoretical justification; their value lies in the intelligence of their making. Precision and care do not diminish the artist’s voice—they sharpen it. In such works, form is not an afterthought. It is the vessel through which meaning becomes visible—and lasting.

In this way, craftsmanship becomes not just a method, but an ethic—a way of approaching the creation of an artwork. In a culture addicted to speed, novelty, and spectacle, the artist’s commitment to slowness, depth, and care offers another way to be and to make. It is a quiet form of resistance—not polemical, but grounded and persistent. Craftsmanship invites us to ask not only what a work means, but how it was made—and why. It reminds us that doing something well is itself a form of meaning.

That is why I want to advocate here for what might be called a “democratization of excellence” in the arts. Defending craftsmanship also means expanding our recognition of artistic value beyond elite institutions, glamorous events, and glossy catalogues. All over the world, in markets, villages, and home studios, artists are shaping wood, clay, metal, fabric, and many other materials with astonishing sensitivity. Their works are not always accompanied by a wall text or theoretical justification. But they speak—through texture, weight, pattern, rhythm, and beauty.

These makers are not “outsiders” to art. They are artists—working within traditions, often outside the mainstream, but no less committed to excellence. Their work does not arise from rebellion against craft, but from mastery within it. Their skill is not self-promotion, but care. In honouring craftsmanship, I want to honour these voices too—people who may not have access to galleries or art schools, but whose work, sharpened through repetition and rooted in tradition, reveals extraordinary beauty and power.

Encouragingly, we are seeing a renewed interest in craftsmanship. Young artists are turning to time-intensive techniques—ceramics, printmaking, textile arts—not as curiosities, but as serious modes of expression. In digital culture too, people are talking about craft: clean code, thoughtful interface design, elegant solutions. Something is shifting. Perhaps, in the face of automation and speed, we are rediscovering the deep satisfaction of doing something well.

Craftsmanship in the arts is not a constraint; it is a form of liberation. It teaches that technique is not the enemy of emotion, that form can carry feeling, and that the trained human hand still has the power to astonish. This is an invitation to value not only the new, but the well-made. Care is not indulgence—it is a kind of respect. In a world rushing ahead, the artist who works with care reminds us: some things are worth doing well.

• Dr Castellote is the Director, Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art. Pan-Atlantic University

Leave a comment