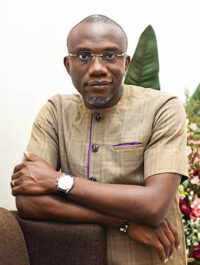

Contrary to insinuations that the military is recruiting repentant insurgents into its ranks, the Coordinator of Operation Safe Corridor, Brigadier General Yusuf Ali, has insisted that they have not been recruited into the military. General Ali explains that the military recruitment process is highly structured, with clear and strict eligibility criteria. He also provided a general overview of the operation and affirmed that there is no possibility of anyone with a criminal background being recruited into the Armed Forces of Nigeria. Linus Aleke brings the excerpts:

You are the Commander of Operation Safe Corridor. Can you give us an overview of the operation?

Operation Safe Corridor began around 2015, when President Muhammadu Buhari assumed office and was keen to explore every possible strategy to reduce the threat posed by insurgents. The idea was not solely to rely on kinetic force but to also introduce non-kinetic approaches. One such approach was to create a pathway for individuals who were not deeply involved in insurgency to surrender voluntarily, thereby reducing the number of active fighters.

How do you identify those who are not hardcore or fanatical insurgents?

You may recall that several local government areas in the Northeast—such as Madagali, Bama, and Gwoza—were once controlled by insurgents. As military operations intensified and these areas were cleared, many insurgents were forced to flee. In the process, they abducted and coerced able-bodied youths from local communities into joining their ranks. Over time, many of these individuals, who did not join the insurgency willingly, began to escape as military pressure mounted. Upon escape, they would surrender to the armed forces, who would take them to designated holding centres for screening and interrogation. During this process, the circumstances under which they joined the group become clearer. Based on these findings, some are categorised as low-risk. On the other hand, the hardcore ideologues rarely surrender unless captured in battle. During their interrogation, it becomes evident that their ideological commitment is deeply rooted.

There are two key pathways for dealing with them. The transitional justice system is applied to low-risk individuals. These are reconciled and reintegrated into their communities after being deradicalised at our centre, rehabilitated, trained in vocational skills, and offered psychosocial therapy. They also receive ideological and religious counselling to help them understand their responsibilities as good citizens.

A combination of therapies is administered before reintegration. The reintegration process is led by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), an independent, non-governmental body that works with local communities, traditional rulers, community leaders, and even victims of insurgency. These stakeholders are brought together to help them understand that some of their sons and daughters, who were coerced into insurgency, have shown genuine remorse and undergone rehabilitation. After a series of consultations and meetings, a reunion is arranged by the IOM, often in collaboration with youth leaders, religious figures, market women, and other key community influencers. Once their buy-in is secured, the reintegration proceeds. In essence, Operation Safe Corridor is a platform for low-risk former insurgents—those coerced into insurgency, who voluntarily surrendered—to be deradicalised, rehabilitated, and reintegrated. Some were even kidnapped while travelling, forced into the bush, and conscripted into the insurgency.

Now to a common question, which often arises with emotion: Why should individuals who participated in the destruction of communities and the killing of innocent people be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society, rather than being subjected to the criminal justice system?

This question stems largely from a misunderstanding of the process. The criminal justice system does apply to individuals who, during interrogation, are identified as ideologues—the masterminds of the insurgency. Many of them have already been prosecuted and sentenced to various prison terms. It is after serving those sentences that some of them may pass through the Operation Safe Corridor programme, having undergone significant therapy and ideological reorientation.

The transitional justice system is reserved for low-risk individuals. The criminal justice system is for high-risk individuals confirmed through multiple sources, including databases, community testimony, and intelligence. In Maiduguri, for example, we have the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), made up of local youth and community members who identify insurgents and hand them over to security agencies.

When individuals are brought into Operation Safe Corridor, the same CJTF members help verify them. For some, they say, “This one was forced into insurgency; he’s not a member.” But for others, they confirm, “He was a commander; he led a camp.” Those identified as high-risk are prosecuted accordingly, and many are currently facing trial. Contrary to public perception, this is not about leniency. Nation-states operate under humanitarian law and are guided by legal and moral obligations. We cannot reduce ourselves to the lawlessness of insurgents. Operation Safe Corridor is a humanitarian effort designed to distinguish between actual insurgents and those who were victims of circumstance.

It could happen to anyone—you or me. One could be kidnapped while travelling, forced into the bush, and coerced into insurgency under the threat of death. Internally, you reject it, but compliance becomes a matter of survival. If such a person later escapes, should they be criminalised by the very society they were taken from? That would be double jeopardy. Operation Safe Corridor exists to prevent such secondary victimisation—giving low-risk individuals a chance to be reformed, reoriented, and reintegrated into society. This is a window of mercy, not for the guilty, but for the victims caught in the crossfire of terrorism.

Do we have statistics on how many of these repentant insurgents have been reintegrated into society? Secondly, are there policies in place to ensure they are monitored after reintegration?

Good question. There are thousands who have been reintegrated and, as I told you, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) monitors their activities. This is because they are the ones who link them with their communities after rehabilitation, using the support of traditional rulers, youth leaders, community leaders, and other key stakeholders within those communities. They are the ones who actually carry out the integration. We only facilitate the process through which they are reconnected with their families after deradicalisation and rehabilitation. However, the monitoring and the broader aspect of ensuring that they live peacefully within their respective communities is handled by the IOM, and so far, there have been no adverse reports concerning them.

We have two models of rehabilitation and reintegration. The Borno model, which is run by the Borno State Government, is not as structured as the federal government’s programme. The federal initiative is known as Operation Safe Corridor, which covers deradicalisation, rehabilitation, and reintegration. However, under the Borno model, the numbers are even higher because insurgents surrender directly to the state government, which then handles their rehabilitation. Since the state is closer to the communities, it’s often more accessible for them. In fact, the number of individuals going through the Borno model is greater than those under Operation Safe Corridor.

From the feedback we’ve received, those who pass through Operation Safe Corridor cannot even return to the bush. This is because the insurgents still in the bush view them as people who have been deradicalised by the government and turned against the group. If they are seen, they risk being killed, as the insurgents believe the government has released them to act as spies. So, the likelihood of them returning to insurgency is practically zero—they wouldn’t survive it.

On the other hand, those under the Borno model do not go through the same close-knit process as Operation Safe Corridor. They have more freedom of movement, and if they feel neglected or unsupported, there’s a possibility that some of them could relapse.

Is the military really recruiting some of them into the service after deradicalisation and rehabilitation, as is being insinuated in some quarters?

There is absolutely nothing like that. To the best of my knowledge, no insurgents are being recruited into the military. The military recruitment process is highly structured, with clear and strict eligibility criteria. You can’t alter the process to accommodate a specific group of people.

There are social and legal qualifications that every applicant must meet to be eligible for recruitment into any of the services. If an applicant has any criminal record, they are automatically disqualified. There is no way anyone with a criminal background can be recruited into the Armed Forces of Nigeria. It’s simply not done.

But why is the military keeping quiet while the rumour is spreading?

The military is not keeping quiet. I am aware that the military has spoken out several times to debunk those rumours. Anybody you see in the military is someone who has followed the strict and structured process of joining. The military does not waive its recruitment policy to accommodate anything that would be inimical to the security of this country.

As the coordinator of the operation, what are some of the challenges you encounter in the process of discharging your statutory duty?

One of the major challenges I face is the press. If you ask me how, I’ve had a lot of discussions with people from the press. It’s just like what the coordinator of the National Counterterrorism Centre was saying the other day—we seem to thrive on sensationalism without considering the fact that we are all working hand-in-glove on issues of national security and cohesion.

We are having this conversation, but you and I know that no activity, whether social or economic, can thrive in an atmosphere of chaos. If there were total chaos now, we wouldn’t even be able to be here, let alone conduct this interview. We are all partners in this. We should be a little less emotional and less sensational when discussing security matters.

The press is one of my biggest challenges because all efforts to make them understand the structured system of conducting deradicalisation, rehabilitation, and reintegration processes seem to be overshadowed by emotion. They do not want to see reason. As I often say, it’s important to sometimes turn the coin a little—try to see things from the other side. Any of us, as I’ve said before, could be victims. We could be travelling, a vehicle could be stopped, and we might be kidnapped and taken into the bush. It is not our will to be there. After being forced into criminality, if we are then given the opportunity to turn over a new leaf, to change, and society chooses to stigmatise us and refuse reintegration, how would we feel? That is the problem.

But once the press understands that what is being done is this: anyone who is deradicalised, rehabilitated, and reintegrated is one less killer among the numbers out there. If they see the programme for what it is—a window for rescuing victims of circumstance who have been forced into insurgency, cleaned up, and reunited with their communities, and who are now contributing positively to the growth and development of their communities—then that would remove the stigma, reduce misinformation and disinformation, and properly inform Nigerians. That would benefit us all.

Beyond the issue of the press and their perception of the programme, what other issues encumber your performance?

It’s not a blanket indictment of the press, as many of your colleagues have been helpful in balancing the narrative, which is commendable. Everything being done is a work in progress. The growing level of buy-in by Nigerians is crucial because, for example, as I mentioned, there are foreign bodies coming to study the initiative. We have the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), which consists of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger—they were here to study the initiative. We currently have a delegation from Cambodia with us, visiting some of our facilities. People from various parts of the world are recognising the good work being done here. However, we Nigerians seem not to see the value of what is being achieved through Operation Safe Corridor. That national buy-in still appears to be lacking, and I don’t think it can be completely separated from the information space—because what people hear informs what they do. So, possibly due to inadequate information, Nigerians have yet to fully appreciate or support what Operation Safe Corridor is doing, and that is a significant challenge.

Again, now that the outside world has seen the positive outcomes of this operation and is seeking to study it to replicate it in their own regions, whereas our own citizens have not fully assimilated or bought into the programme, do you have sufficient funding to embark on aggressive advocacy to ensure that citizens also fully support this noble initiative?

Advocacy should not be dependent on funding. Advocacy should be about people being willing to listen—because if people are not ready to listen, no matter how much you spend, it will not achieve the objective. For example, I was supposed to attend other engagements, but the moment you told me you wanted to have a discussion with me, I prioritised it and left everything else I had planned—because I know you have an audience, you have a voice, and this is part of advocacy. I have told you what we are doing, and I am hopeful that you will also use your platform to better educate Nigerians. And in doing so, it doesn’t have to be about money; it should be about the desire to be a partner in the good work being done to advance peace and security in our country. So, when more people in the press are willing to listen, to understand what is being done, and to engage dispassionately, I believe it will no longer be a challenge—it will become an opportunity for progress.

We also carry out other non-kinetic operations to win the hearts and minds of the populace. We provide relief materials, carry out various outreach activities, and engage in civil–military relations. We have a wide range of activities that are also capital-intensive. We must understand that, as human beings, we will inevitably face limitations, particularly in terms of finance and other critical resources. That said, within the scope of what is available, I have never really considered money to be a major obstacle to achieving something—especially when there is the will to get it done, and particularly when it comes to telling the truth about a particular situation.

Finally, sir, what would you say has been your high point since your appointment?

The Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), General Christopher Musa, who strongly believes in what Operation Safe Corridor is doing, has been immensely supportive and is a passionate advocate for the non-kinetic approach to tackling insurgency. If you listen to most of his public statements, he consistently emphasises that fighting and defeating insecurity is less than 30% a military effort. The remaining 70% or more depends on good governance, national cohesion, and a whole-of-society approach—where every Nigerian takes responsibility and contributes, no matter how small.

Insurgency thrives on people; its oxygen is the people. That is why insurgents do everything possible to undermine the trust of citizens in their government. My highest point has been the belief and confidence of my principal, the Chief of Defence Staff and Chairman of the National Steering Committee of Operation Safe Corridor, in the non-kinetic approach. He has been unwavering and tremendously supportive of any initiative aimed at achieving our goals.

Leave a comment