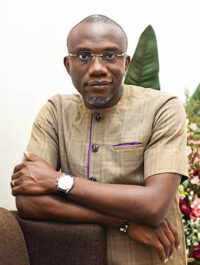

Ezeh Emmanuel Ezeh

In a land where the sun rises on empty stomachs and weary hearts, the recent proposal by the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC) to increase the salaries of political leaders feels like a cruel joke, one told at the expense of the very people who hold this nation together. It is not just insensitive. It is a betrayal. As Mr. Peter Obi rightly pointed out, this move exposes a greed so deeply rooted it has become policy – raising the comfort of the few while the many are left to choke on dust and broken promises.

In 2015, the Nigerian minimum wage stood at N18,000, then worth about $120. It wasn’t much, but it was enough to buy a bag of rice, pay for transport, and maybe save a little for emergencies. It was a fragile lifeline, but it held. Today, that same N18,000 barely buys a week’s worth of provisions. With the naira now hovering around N198,000 for the same $120, the Nigerian worker is stranded in a desert of despair, watching the mirage of a better life fade further into the horizon.

Behind the statistics are real people. They are flesh and blood, dreams and disappointments. Professor Nwigwe teaches Geophysics at a federal university in the South-east. He earns N525,000 a month which is roughly $318. For a man who has spent decades shaping minds and building knowledge, it’s a cruel mockery. His hope now lies not in research grants or academic recognition, but in election seasons. That is when he can sells off a piece of his family land to secure an appointment as a INEC returning officer. In three chaotic days, he can earn what would otherwise take him years. He knows the game: take bribes, rig results for rogues, charlatans, and walk away with enough to finish his long-abandoned bungalow in his village. It’s not pride that drives him. It’s desperation.

In Kaduna, Musa wakes before dawn. Not because he’s eager to teach, but because he must trek five kilometers to school—he can’t afford the N750 daily transport fare. His N105000 salary vanishes within days. Rent swallows half. Electricity bills, though erratic, demand their share. What remains barely covers food and the occasional paracetamol. His students sit on broken chairs, scribbling in reused notebooks. Chalk is a luxury. One day, Musa collapsed in class—not from illness, but from hunger. The principal handed him N1,000. Musa cried—not from gratitude, but from the humiliation of begging in the very place he was meant to inspire.

Ngozi, a nurse in a government hospital in Abia, works 12-hour shifts, sometimes longer. She’s watched patients die—not because she lacked the skill, but because the hospital lacked gloves, syringes, and antibiotics. Her N35,000 salary cannot stretch across transport, feeding, and school fees for her two children. Last month, her son was sent home for unpaid fees. She pleaded with the school, offering to pay in bits. They refused. She broke down in the headmaster’s office, clutching her ID card like a shield. “I’m a nurse,” she whispered. “I save lives.” The headmaster looked at her with pity. “But who will save yours?”

While Musa and Ngozi wrestle with hunger and humiliation, Nigeria’s political elite bask in obscene luxury. Senators earn millions monthly, excluding generous allowances. They fly private jets, host lavish parties, and send their children to elite schools in London, Toronto, and Dubai. Their homes are monuments to excess: marble floors, imported chandeliers, fleets of SUVs. When the topic of minimum wage arises, they respond with chilling detachment. “It’s not feasible,” they say, sipping champagne. “The economy is struggling.” Yet that same economy funds their wardrobe stipends, travel allowances, and security votes. The disconnect is staggering. Nigerian workers aren’t just underpaid, they are unseen! Invisible!!

I fear that what is unfolding before us is a haunting echo of the French Revolution. While the elite luxuriate in presidential yachts and jets, the masses starve. Today’s leaders mirror Queen Marie Antoinette; indulgent, aloof, and dangerously out of touch. “Let them eat cake,” Queen Marie once said, oblivious to the fact that those who can’t afford bread cannot dream of cake. That ignorance sparked a revolution, one that tore through feudal privilege and gave birth to the eternal cry: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité. The guillotine became a symbol not just of rage, but of reckoning. No society survives when the majority starves and the minority feasts.

Centuries later, Nigeria teeters on its own precipice. The political class remains aloof, squeezing citizens dry with taxes while offering little in return. Social services crumble, yet the appetite for revenue grows. The people are stretched to breaking point.

In Lagos, the average worker spends three hours daily in traffic. By the time they reach the office, exhaustion has already set in. Lunch is a rushed N800 plate of rice and beans, eaten without joy. At home, darkness awaits—NEPA has struck again. The generator hums, but fuel prices have doubled. So they sit in the heat, fanning themselves with old newspapers, dreaming of escape. Many take on side gigs—Uber driving, selling recharge cards, freelance writing—but even these are oversaturated. The hustle never ends. Weekends are for laundry, church, and mental recovery. Vacations? A myth. Retirement? A looming fear.

After decades of service, many Nigerian workers retire into poverty. Pensions are delayed, sometimes for years. Retirees queue under the scorching sun for verification exercises, clutching documents like lifelines. Some collapse. Some die. Their families mourn not just their passing, but the indignity of their final years.

Baba Sule, a retired local government worker, waited five years for his pension. He survived on handouts from neighbours. When he finally received N1.8 million, he used it to buy a secondhand wheelchair. His legs had failed him after years of untreated diabetes.

Mrs. Nwakaego returned from the farm one afternoon to find her husband lifeless. He had never recovered emotionally after the government demolished his shop to make way for a dual carriageway – on a road so desolate, one could count the number of vehicles that passed. The business was his lifeline. When it vanished, so did his will. Since then, Nwakaego has shouldered the burden alone, selling vegetables in front of their rented apartment. Today, the circle tightens even more: Widowed. Poor, and desperate.

Beyond financial strain lies a deeper emotional toll. Nigerian workers battle depression, anxiety, and hopelessness. They smile through pain, laugh through tears, and pray for miracles. Politicians urge them to “tighten their belts” while loosening theirs. Workers are told to be patient, patriotic, and enduring. But how long can one endure starvation, humiliation, and neglect?

President Tinubu’s recent remarks, shifting blame to governors and claiming he’s “doing everything to raise revenue” ring hollow. His reforms seem focused on extracting more from the people, not empowering them. And while he points fingers at fellow indulgent governors, his ministers pursue bizarre priorities: N146 billion earmarked for bus terminals in zones where there are no roads to reach them, N14 trillion for coastal highways while citizens sleep on kidnapping-infested roads between Ore and Benin.

Yet the indignity of the Nigerian worker is not entirely lost on the APC, which has resorted to another round of palliative theatrics. Governor Hope Uzodimma recently announced a new minimum wage of N104,000, roughly $65 or £49, barely enough to cover basic monthly expenses. Governor Nwifuru, while constructing extravagant underground tunnels, declared a N90,000 wage, about $54 or £42, in a state where economic activity has ground to a halt under his administration.

And yet, despite it all, the Nigerian worker remains resilient. They show up. They teach, heal, build, clean, and serve. They raise children with values, even when the system offers none. They protest, vote, and speak out. Their spirit is battered but not broken. That is the tragedy and struggles of the Nigerian worker.

They deserve more. Not just a living wage, but a life of dignity. Let RMAFC not become the historic Queen Marie Antoinette that ignites the spark leading to revolution and social unrest.

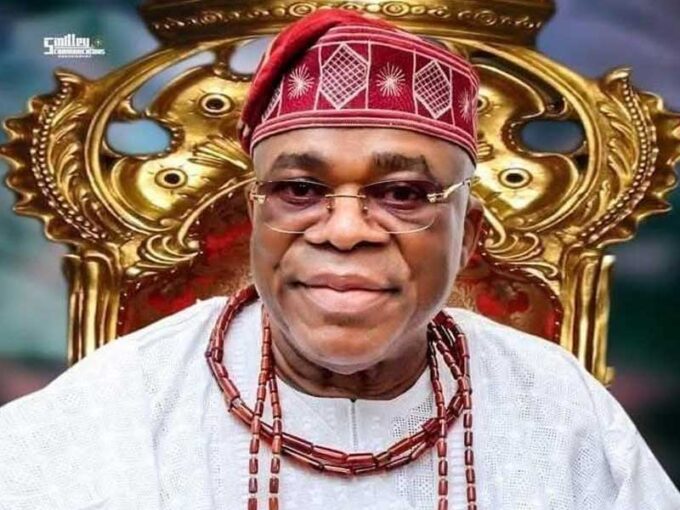

• Dr. Ezeh, President of the Ebonyi State Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture (ECCIMA), writes from Enugu

Leave a comment