From a childhood split between the order of Yaba and the hustle of Ajegunle to leading a company bringing solar power to millions, Kola Osinowo’s life is about precision, purpose, and the

belief that leadership begins with service, writes Vanessa Obioha

Tuesdays are for execution in the world of Kola Osinowo, the Group Chief Executive Officer of Izili Nigeria Limited (formerly Baobab+). On the Tuesday afternoon we met, Osinowo had already ticked off several items on his to-do list, even something as simple as drinking a cup of water. But what stood out wasn’t the checklist; it was his precision with time. For 17 years, Osinowo has maintained an unbroken routine that sees him resume work by 7am and is often the last to leave, sometimes as late as 9pm. On his final day at his previous job, he personally handed the office keys to the security guard, a symbolic gesture of closure.

That discipline, he said, runs in the family. His late father, an engineer who shuttled between England and France, was a stickler for time. He arrived early for every event, stayed only as long as he wished, and left on time, regardless of when the occasion began. His mother, a medical practitioner, also lived by the clock, accustomed to hospital shifts that demanded precision.

Osinowo’s early years at Command Day Children School, Yaba, and Command Day Secondary School, Ikeja, further reinforced that culture of order. In another life, perhaps, Osinowo would have achieved his dream of becoming a soldier.

He once dreamed of attending the Nigerian Military School but was dissuaded when a family friend — a military officer — left the school and was deployed to CDSS Ikeja. Later, he even earned a scholarship to join the UK Army, but his mother refused to let him go.

Before then he joined the Nigerian Army Cadet. Once, he fantasised about becoming an architect but did not pursue the dream.

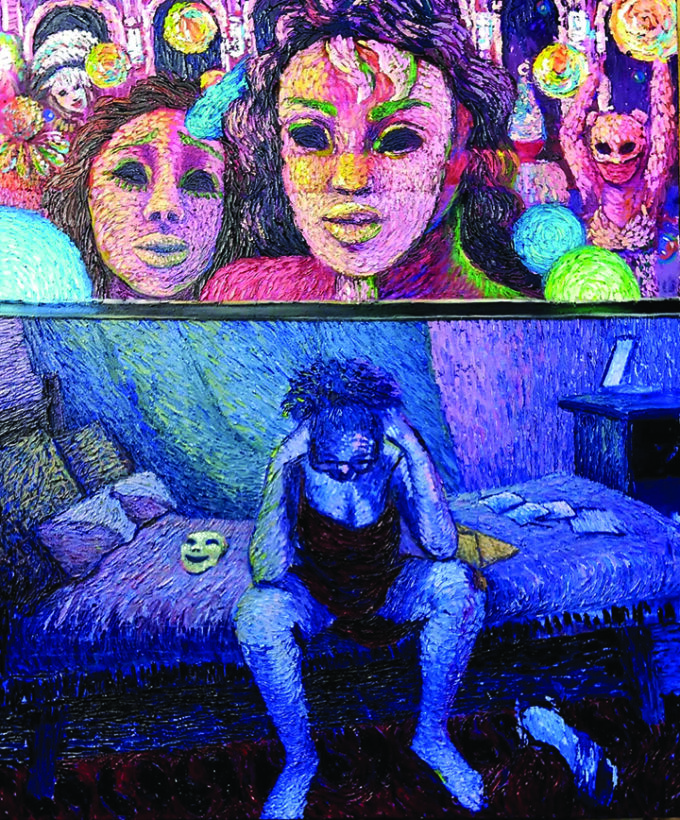

Osinowo came from a privileged background. Yet his parents made sure he also understood life beyond privilege.

“I’m a nepo (nepotism) baby. But my parents also taught us to see the lapo (little access to privilege and opportunities) side of things.”

Every holiday, his parents sent him to his grandmother’s house in Ajegunle where he learnt to hustle.

“My grandmother had a shop there. She was a major wholesaler of bread. We would go and hustle for bread at the bakeries from 5 a.m. From Idowu Street all the way to Boundary.”

The household teemed with over 22 children and four wives; his grandmother was the third wife.

For young Osinowo, the contrast between the comfort of Yaba and the chaos of Ajegunle was transformative. He remembered looking forward to holidays because according to him, “it was an adventure for me.”

“The experience of sitting in the dining room and having my own bowl of meal at home to where you have to sit down on the floor with like 10 other children eating from a tray because they were from the north. Her husband was from the north. So that communal living was there,” he fondly recalled.

“Then my cousins were all male,” he continued, “so that adrenaline was there. The adventure of looking for bread, carrying that big basin on your head, okay? And if the sales were not moving, we used to bring the bread to Wilma Junction to sell it ourselves. Just that chaos there which I didn’t experience in my house.”

In his house in Yaba, the activities were often limited to a swim in the University of Lagos and Sunday trips to Ikoyi Club where his father was a member.

Those experiences taught him resilience, empathy, and enterprise.

“I saw poverty firsthand there,” he said. “People struggled but I also learnt hustling there. I learnt that entrepreneurial spirit from her.”

By university, the lessons had taken root. As a student of Electronics and Computer Engineering at the Lagos State University, Osinowo taught himself web design and turned it into a thriving business. “I was making six times my salary,” he said.

At one point, he resigned from his job.

“I worked from Friday to Sunday, training people at Lagos Digital Village. My dad got worried that I was home all week and thought I’d gone into cybercrime. He insisted I get another job, that I have to work every day.”

That push kept him grounded. Over the next two decades, Osinowo rose through leadership positions at Microsoft, Jumia, Nokia, and HMD Global, gaining a reputation as a disciplined, strategic, and empathetic leader. He attributed these qualities to his military school background and the leaders who mentored him along the way. A voracious reader, the data analyst has penned leadership books which were displayed in one corner of his office. His latest is on adaptive leadership where he explores managing moral tensions in the corporate world while navigating rapid change.

In his current role as the GCEO of Izili Nigeria, Osinowo is at the forefront of scaling renewable energy and digital inclusion solutions in African markets. Izili is known as a purpose-driven last-mile distributor of solar energy systems and digital products in Africa. Since 2015, the company has illuminated over two million homes.

Electrification, however, remains a worrying headache in Nigeria as most rural and urban areas are yet to be illuminated. With less than five years to achieve the United Nations SDG 7, which advocates for universal access to energy, Osinowo placed Nigeria’s efforts in reaching that goal at six on a scale of 10.

“We are the least electrified country in the world if you look at it in terms of the numbers. There are still over 85 million Nigerians without electricity today,” he explained. “The next closest is DRC, and there’s a 35 million gap between Nigeria and DRC in terms of people that are not electrified.”

Unlike in other countries where energy deficit is often seen in rural areas, in Nigeria, it is seen in both rural and urban areas. This makes Nigeria’s electrification problem more complex.

“It is not just energy access, it’s also energy reliability. Now, we’ve added a third component, which is affordability. Where I used to live before, I used to pay, probably, for argument’s sake, let’s say N20,000. Today, I may probably pay N200,000 per month but I have the electricity because I’m in band A.”

Izili, he said, tackles the problem from all angles.

“For accessibility, we focus on rural and peri-urban areas that have never seen a power pole,” he says. “That’s where we deploy solar home systems — simple setups that let families light their homes, charge their phones, and listen to the radio.”

He acknowledged the government’s efforts in solving electricity accessibility through the Rural Electrification Agency. Recently, at the Nigeria Renewable Energy Innovation Forum 2025 held in Abuja, the agency, in partnership with the federal government and some state governments, secured renewable energy investment agreements with private sector players and development partners. The agreements valued at US$435M are expected to help Nigeria reach its targeted goal of 277 gigawatts of installed electricity capacity by 2060.

But he believes state governments, now empowered to generate electricity, must also be held accountable. “It’s not just about generation,” he insists. “We need distributed renewable energy — decentralised systems that reach the last mile. That’s where companies like us come in, combining technology with financial inclusion through pay-as-you-go models.”

In rural areas, access to solar power often provides more than light. It opens doors to banking and digital services. “For some of our customers, owning a solar product means opening their first bank account,” Osinowo explained.

For businesses, it is more about electricity reliability, knowing that they have solar-powered appliances that can help keep their business going.

Profitability in renewable energy is still not convincing to some investors. Instead of switching on the bulb and going all in, some investors are still feeling their way with a torchlight.

“So profitability is still an issue within the industry, and that’s why for us now, we’re advocates of consolidation within the industry. There are too many small players that cannot raise funds on their own. What we’re trying to do now is to say to all these smaller players that we have a platform. ‘We’re in four countries. Can you join us?’”

As a last-mile distributor, Izili also grapples with challenges — logistics, infrastructure, and security among them. But Osinowo and his team remain undeterred, promoting clean energy solutions such as clean cooking products that reduce the use of firewood.

When our conversation wound down, Osinowo reflected on his unconventional journey; from the boy who wanted to be a soldier to the man leading an energy revolution.

“I am unlimited by design,” he said confidently.

If there is one principle his mentors taught him that he lives by, it is to have the depth of knowledge, “which is the expertise, and a breadth of knowledge, which is to be able to move across industries.”

Leave a comment