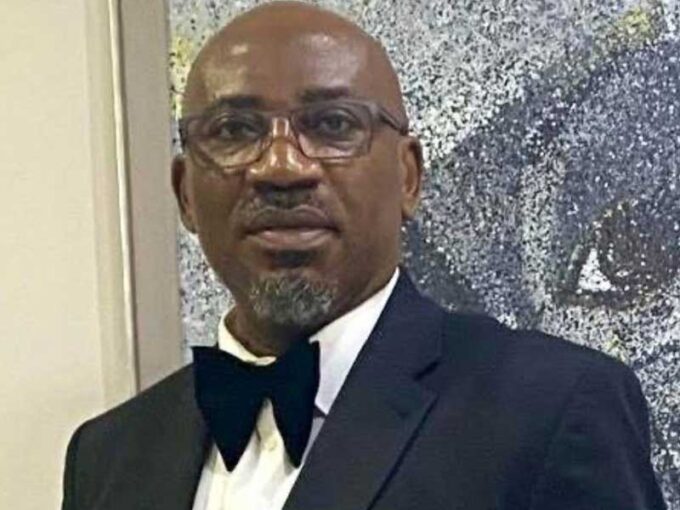

By Abubakar Bukola Saraki

It is an honour and a responsibility to join you for this timely conversation—not simply as a former public servant or as someone who has worked across banking, healthcare, entrepreneurship and governance—but as one who believes deeply in Africa’s future, a future defined by our innovation, our institutions, our people. The theme before us today—Ending Dependency: Rethinking Africa’s Path to Prosperity—goes to the heart of the African question. It invites us to examine the foundations of our political economy, the architecture of our governance, and the mindset that has shaped our collective trajectory since independence.

Africa’s Context and Potential

More than six decades after the first African nations achieved sovereignty, the project of full independence—economic, political, and intellectual—remains unfinished. Our economies still echo colonial designs: systems of extraction and export, where raw materials leave our shores at minimal added value and return as finished products commanding prices we do not control. Our fiscal policies are often shaped by external interests, our monetary stability sometimes dependent on foreign institutions, and our development agendas influenced by external prescriptions rather than internal aspirations.

Yet, the potential is unmistakable. Africa comprises about 54 sovereign states, with a median age often under 20 years in numerous countries. For example, Nigeria’s median age is around 19 years compared to approximately 32.6 years in the United Arab Emirates. We are home to immense natural resources—from minerals such as cobalt, lithium, bauxite, timber and agricultural produce to renewable energy potential. We also possess a large internal market—an aggregate population of around 1.4 billion people—which gives us a regionally grounded demand base larger than many emerging economies. If harnessed, this demographic and resource “dividend” can become a source of prosperity—but unmanaged, it can equally become a source of unrest, frustration and wasted promise.

This forum is timely because it recognises that ending dependency will not happen by chance. It requires intentional deliberate effort, collective will and a disruption of the status quo.

How Did We Get Here?

To chart the way forward, we must first understand how our continent arrived at its current state of dependency. This section explores the historical foundations, institutional weaknesses, leadership deficits, financial and aid dependency, and misaligned priorities that have shaped our trajectory. Historical Foundations At independence, many African states inherited governance structures transplanted from colonial powers: the British Westminster-parliamentary model, the French parliamentary system, Belgian Constitutional monarchy design, Portuguese semi-presidential administration and others. Today, Africa’s 54 countries operate under varying political models: roughly 20 are presidential democracies, 13 are parliamentary, 7 are semi-presidential, 6 are under military leadership, and the remainder are monarchies or hybrid systems such as in Morocco, Eswatini, and Ethiopia’s federal arrangement. These systems were not always designed for the realities of Africa’s diverse societies. The colonial rule itself rested on a logic of divide and rule and extraction: political power was centralised, local institutions weak or subordinate, and economies engineered to serve the colonisers rather than develop local capacity.

The consequence is that we inherited not only the infrastructure but the institutional mindset of extraction rather than empowerment, of outflows rather than reinvestment. This legacy remains visible in many governance, economic and institutional practices today.

Institutional Weakness

Over the decades, many of Africa’s post-independence structures — instead of evolving into instruments of stability and accountability — have matured into sources of institutional weakness. The colonial architecture of governance, designed for control rather than development, left behind fragile systems that too often failed to adapt to democratic and developmental imperatives.

In many states, the judiciary remains under-resourced and vulnerable to political influence, while parliaments are either weak or overshadowed by dominant executives. Political parties, rather than being ideological institutions that outlast individuals, often revolve around personalities and patronage networks. Legislative oversight is minimal; executive dominance is the norm.

This erosion of institutional checks and balances has had profound consequences. It is what allows, for instance, the re-election of Paul Biya in Cameroon at the age of 92, and the perpetuation of similar political dynasties in Equatorial Guinea and other nations, where power remains concentrated in the hands of a few rather than distributed through accountable systems. These are not merely political anomalies — they are symptoms of institutional fragility.

Put simply, when institutions are weak, vision is easily short-circuited and dependency entrenched. Governments lose the capacity to review, innovate, or chart new developmental pathways. Policies become reactive rather than strategic; governance becomes transactional rather than transformational.

Leadership Deficits

Leadership matters — profoundly. For decades, too many of Africa’s leaders, with all due respect, have held power without the strategic vision to invest in long-term transformation. Public office has too often been treated as a possession rather than a stewardship — a means of control rather than a platform for service.

This absence of foresight has had far-reaching consequences. Policies, plans, and projects frequently collapse when administrations change hands, not because they lacked merit, but because they bore the mark of a previous government or political party. Across the continent, billions of dollars’ worth of infrastructure projects lie abandoned — uncompleted highways, stalled hospitals, unfinished schools, and silent industrial zones — victims of political discontinuity.

This pattern reflects a deeper malaise: leadership not guided by ideology and party loyalty rather than national transformation. When governance is driven by politics instead of purpose, progress becomes fragmented, and resources are squandered. Leadership then becomes reactive, short-term, and self-preserving — geared towards retaining power rather than building for generations.

Yet, responsibility does not rest on leaders alone. Citizens — the followers — have not always demanded the quality of leadership that drives structural change. When accountability is weak, complacency thrives. A society that tolerates mediocrity in leadership inevitably pays the price in stagnation.

The result has been a cycle of short-termism, where successive governments prioritize immediate visibility over enduring value, and where national plans lack continuity. To break this cycle, Africa needs a new generation of visionary and ethical leaders — who see beyond electoral cycles to the broader horizon of transformation.

True leadership is not measured by tenure, but by the foundations it lays for those yet to come.

Financial and Aid Dependency

Another pillar of our dependency is the pattern of financial flows. Foreign aid and concessionary loans, while often labelled as help, have frequently entered without sufficient transparency or accountability. I experienced this myself when, as Senate President, I challenged the executive on foreign‐loan approvals and received political push-back because the system did not support proper scrutiny of purpose or impact.

Many of these loans are accepted as if they are free gifts, yet repayment obligations remain. Worse still, donor agencies regularly design programmes that create jobs or markets for their own countries rather than the recipient African economies. This means the aid model often perpetuates dependency rather than ending it.

Misaligned Priorities

Finally, our aid and development agendas have too often been driven by external interests rather than our own needs. Take healthcare as an example: despite malaria being one of Africa’s highest morbidity burdens, much health aid has gone instead to HIV/AIDS programmes, not always because that is the continent’s primary need, but because of donor priorities. Many materials, vaccines and programmes end at national capitals and fail to reach villages, towns and states where the need is greatest. This mismatch reinforces a model of dependency rather than empowerment.

Where Are We Now?

Today, we stand at a pivotal moment. The global order is shifting. The rise of China and India, the growing influence of the Gulf States, the evolution of the European Union, and the expansion of regional blocs such as BRICS Plus mean that the world is no longer unipolar. Africa is again at the centre of global attention—not as a passive frontier but as a strategic frontier.

Our resources, critical minerals for clean energy, renewable capacity, youthful population—all position the continent as one of the most coveted investment frontiers of the 21st century. The central question before us is simple: Will Africa let the world shape its future—or will Africa shape the future?

We must redefine prosperity not in terms of exports or GDP growth alone, but in how much value we retain within our borders, how strong our institutions become, how inclusive our economies are, and how much dignity and opportunity we create for our people. Prosperity rooted in production, innovation and resilience—not extraction and dependency.

What Must Be Dismantled: The Pillars of Dependency

To end dependency, we must confront its economic, institutional and psychological foundations.

Economic: We must replace extractive models with productive ones. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is not merely a trade agreement—it is a vehicle for industrial cooperation and continental self-sufficiency. Currently, intraAfrican trade represents only about 14.9% of the continent’s total trade. Compare that with Europe’s intra-region trade share above 60% or Asia’s above 50%. This gap is an opportunity.

Institutional: We need institutions that outlive individuals. Transparent budgeting, legislative oversight, fiscal accountability are not optional—they are liberation tools. My own experience as Senate President in Nigeria underscores how institutional reform is central to sovereign capacity.

Psychological: We must end the mindset that progress must come from elsewhere. Africa must trust its own competence. Our entrepreneurs, researchers and innovators are already developing world-class solutions to local and global challenges. They need enabling environments: infrastructure, financing and policies that reward—not constrain—creativity.

Benchmarking Success: The Gulf States Example

To bring clarity to what is possible, let us look at benchmark economies, particularly the Gulf States such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). These states once relied heavily on raw oil exports. Instead of remaining mere exporters of crude, they:

• Created sovereign wealth funds managing hundreds of billions of dollars (e.g., the UAE’s Mubadala manages over US$300 billion).

• Invested strategically in manufacturing, technology, infrastructure and services.

• Developed governance and infrastructure systems suited to their context— they did not merely copy Western parliamentary models but adapted their governance structure to their realities.

The model shows us two key things: First, resource abundance is not a curse—it is an opportunity when strategically deployed. Second, governance, purpose and reinvestment matter more than mere rents.

Africa’s demographic advantage, natural-resource breadth and internal market size exceed those of many Gulf states. First, demographics. Africa’s median age is just 18.8 years, compared to about 33 years in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. This youthful population represents not only labour but potential in creativity, innovation, and resilience that can drive industrial transformation for generations.

Second, resource diversity. Unlike the Gulf States, whose economies depend predominantly on hydrocarbons, Africa possesses a far more diversified resource base — from the cobalt of the DRC to Nigeria’s gas reserves, Ghana’s gold, Guinea’s Bauxite, Kenya’s geothermal energy, and Zambia’s copper. We hold over 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, 12% of oil, and 8% of natural gas, alongside vast agricultural and renewable energy potential.

Third, market scale. Africa’s internal market of 1.4 billion people, projected to reach 2.5 billion by 2050, represents the largest untapped consumer and industrial base in the world. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), once fully operational, will create a single market valued at over $3.4 trillion, capable of catalysing intra-African trade and manufacturing at an unprecedented scale. If we adopt the discipline they applied—in governance, reinvestment and strategy—we can surpass their trajectory.

What Must We Do: A Roadmap for the Future Now let us turn to actionable imperatives—what Africa must commit to—and the impact if we execute effectively.

a) End Raw Material ExportsWe must firmly say no to the automatic export of raw commodities. Instead, we must invest in processing, manufacturing and finished-goods production. From:

• Lithium ore to battery production in DR Congo • Cocoa beans to chocolate and confectionery in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire • Bauxite to aluminium products in Guinea

• Cotton to textiles in Benin Republic

• Soya bean to animal feed and processed food in Nigeria

• Timber to furniture and finished wood products in Gabon

When African countries export raw materials—whether lithium ore, bauxite, cocoa beans or timber—we forfeit vast economic and social opportunities: lost jobs, lost income, lost value-chain capture, lost technology development.

Countries exporting raw cocoa receive the commodity price; but when processed into chocolate or finished foods, the value multiplies several times. By exporting only raw cocoa, a country leaves processing jobs, technology, branding and higher margin profits to others. For example, while Africa accounts for over 70% of global cocoa production, it captures less than 5% of the $130 billion global chocolate market. Also, Nigeria, which supplies about 40% of the world’s raw shea-nuts, holds only about 1% of the global shea-products market (US$6.5 billion). Similarly, Africa exports crude oil and imports refined petroleum at a cost exceeding $20 billion annually, according to the African Refiners and Distributors Association. Despite having over 25% contributions to world reserve in Bauxite, and 23% of world’s production of Bauxite, only 2.25% is being refined in Africa, indicating a loss of value. For instance, we export bauxite at $65/ton and import aluminium for $2300/ton; showing we dig for others to profit because we are trapped at the bottom of the value chain while others build on it. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces a large share of cobalt, copper and other rare-earth minerals but only refines 7% locally.

The World Bank estimates that Africa loses over $100 billion each year in potential earnings due to lack of local value addition across key commodities. This is money that could have built factories, financed education, or powered small and medium enterprises. This illustrates how raw-export status limits value capture and employment creation. Other than the obvious economic loss, there are several other socio-economic disadvantages. Manufacturing and value chains create far more employment than raw commodity extraction. For every million dollars of mining export revenue, you may get a few dozen jobs; but for a million dollars of finished-goods exports you could generate hundreds of jobs in processing, logistics, marketing and services. Also, the difference between raw exports and value-added lies in domestic retention of profits, taxes, technology transfer, and multiplier effects in the economy (supplier networks, skills development, secondary industries).

In essence, value-adding within Africa means local communities benefit, ownership increases, supply chains are internalised, economies diversify and dependency declines. The impact is that jobs increase locally, export revenues rise through higher margins, technology and brand development become African-led industries. It means Africa shapes its future instead of being shaped by external demand.

b) Strengthen Domestic Resource Mobilisation

To achieve true economic sovereignty, Africa must build strength from within — by deepening and fortifying its own financial architecture. This means empowering our banks, development finance institutions, pension funds, and local capital markets to become engines of growth driven by African capital. History has shown us that no nation or continent has ever achieved sustainable development on borrowed capital. The remarkable rise of institutions such as the African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIM Bank) proves what is possible when African finance serves African ambition. Growing its asset base from just over US$6 billion in 2015 to C.US$44 billion today, AFREXIM Bank has financed transformative infrastructure, energy, and industrial projects while pioneering tools like the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), which enables trade in local currencies and reduces dependence on foreign intermediaries. It has also championed the establishment of the Africa Energy Bank (AEB) with a unique mandate

This model of African-led finance offers a blueprint for the continent’s future. By strengthening homegrown institutions and aligning them with robust pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and regional capital markets, we can create a selfreinforcing cycle of African savings, African investment, and African growth. With stronger domestic finance, our nations will depend less on external debt, weather global financial headwinds with resilience, and invest boldly in our priorities — from clean energy to manufacturing to human capital. This is how Africa transitions from dependency to destiny — by financing its own future and shaping its own path to shared prosperity.

c) Boost Industrialisation and Export-Led Growth

Africa’s industrial future will determine its economic destiny. At present, manufacturing contributes roughly 12% of GDP across many African economies — a modest figure compared to the 20–22% achieved by other emerging markets in Asia and Latin America. Closing that gap is not merely a numerical target; it is a strategic imperative for structural transformation.

To raise manufacturing’s share of GDP, we must create an enabling environment where industry can thrive. This means developing industrial parks and export processing zones with world-class infrastructure, ensuring stable energy and logistics systems, and embedding quality assurance and standards institutions that make African goods competitive globally. It also demands investment in value-chain clusters that link small enterprises to larger manufacturers — so that local farmers, artisans, and service providers all become part of an integrated production ecosystem. On quality assurance and standards, beyond the hard infrastructure, Africa must also focus on the softer, yet foundational enablers of trade competitiveness. Governments must invest in robust standards and certification agencies to ensure product quality, traceability, and compliance with international benchmarks. Collaborations with EU and U.S. regulatory bodies can fast-track export readiness and market access.

Equally vital is human capital. Industrial transformation cannot be imported; it must be built through technical education, vocational training, and digital skills that prepare our young workforce for modern production technologies. When manufacturing grows, the results cascade: higher incomes, job creation, diversified exports, and resilience to commodity price shocks.

Industrialisation is not simply about factories — it is about dignity. It is how nations shift from exporting raw potential to exporting refined value; how they move from vulnerability to strength. Building Africa’s manufacturing base is thus both an economic necessity and a continental calling.

d) Promote Intra-African Trade and Market Integration No region in the world has ever prospered by trading little with itself. Yet, Africa’s internal trade currently accounts for only about 14–15% of total trade, compared to about 60% in Europe and 50% in Asia. In 2024, intra-African trade stood at approximately US$220.3 billion — a promising but insufficient figure for a continent of 1.4 billion people and immense productive potential.

To unlock our true market power, we must break down the artificial borders that fragment our economies. This means simplifying customs procedures, harmonising regulations, and building integrated transport, logistics, and digital payment systems that make it as easy to trade between Lagos and Nairobi as it is between Berlin and Paris.

At the heart of this transformation lies the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) — the largest free trade area in the world by population. The launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) presents an opportunity to transform intra-African trade from just 15% of total exports to over 50% by 2030. With effective implementation, AfCFTA can enhance regional integration, industrialization, and economic resilience, while boosting the continent’s global bargaining power. But its promise will only be realised through implementation: by aligning national policies, investing in cross-border infrastructure, and empowering African enterprises to compete regionally and globally.

When we trade more with one another, we create larger economies of scale, develop regional value chains, strengthen our bargaining power in global markets, and foster inclusive, broad-based growth. Intra-African trade is not just an economic agenda — it is a political and developmental necessity. It is how we turn the idea of African unity into a tangible engine of prosperity.

e) Mobilise Local Capital and Leverage Diaspora Remmittance/investment

For too long, Africa’s growth story has been written by others — shaped by foreign aid, venture capital, and private equity seeking quick returns and fast exits. Yet the continent’s true promise lies not in short-term capital flows, but in patient, longterm value creation. Ending dependency requires us to reimagine the role of finance — not as a handout, but as a partnership rooted in shared purpose and African agency. The future of African prosperity depends on unlocking the wealth that already exists within our borders, across our diaspora, and within our family offices. While private credit has grown into a $1.6 trillion global asset class, less than 1% is directed toward Africa — a glaring gap that underscores both the challenge and the opportunity before us.

Africa’s diaspora alone remitted over $95 billion in 2024 according to the State of Africa’s Infrastructure Report 2025 by the Africa Finance Corporation — nearly matching the continent’s total foreign direct investment. This is not just a testament to economic resilience; it is proof of enduring trust and connection. By mobilising this capital alongside domestic pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and institutional investors, we can deepen Africa’s financial markets, empower homegrown institutions like the AfDB, AFREXIM Bank and the Africa Energy Bank (AEB), and attract global investment on African terms. The path forward is clear: Africans must invest in Africa. Foreign capital can complement, but it must never substitute local ownership. This is more than economics — it is a declaration of independence. Africa’s next chapter will not be written by aid, but by Africans — as co-creators of prosperity, architects of our destiny, and stewards of a new era of sustainable, self-driven growth.

f) Invest in Human Capital and Innovation

Africa’s greatest asset is not beneath its soil but within its people. With over 60% of Africans under 20, the continent holds unmatched human potential — but a youthful population is not automatically a dividend; it is a duty. To turn this energy into prosperity, Africa must invest boldly in education, digital skills, and innovation. Building strong foundations in STEM, entrepreneurship, and research will equip young Africans to compete globally and create locally — transforming the continent from a consumer of ideas to a producer of innovation. By nurturing ecosystems that empower creativity — from tech hubs and agri-tech labs to renewable energy and fintech enterprises — Africa can reduce dependence on imported technology, retain its brightest minds, and drive homegrown solutions to its challenges. The demographic dividend will not unfold by accident; it must be cultivated with vision and purpose. When Africa invests in its youth, it invests in its independence — because the future of the continent will be written not by aid, but by the ingenuity of its people.

g) Leadership and Governance

At the heart of every nation’s rise lies leadership — deliberate, visionary, ethical, and strategic leadership. Africa’s transformation depends not on chance, but on the quality of governance that plans for generations, not tenures. Leadership must transcend politics and personality; it must become a solemn commitment to stewardship, integrity, and nation-building.

Good governance is strategic capital. It is what sustains investment, inspires trust, and drives long-term progress. When leadership is accountable, when public institutions are strong and transparent, confidence grows — not only among citizens, but also among investors, innovators, and partners.

Yet if corruption, weak institutions, and short-term thinking persist, every other reform — in trade, industry, or education — will falter. Governance is the foundation upon which all else rests.

By nurturing ethical leadership, stronger institutions, and a culture of accountability, Africa will unlock higher investor confidence, improved public sector performance, and greater national resilience. The true measure of leadership is not the power it wields, but the legacy it leaves behind — a legacy of continuity, credibility, and transformation for generations yet unborn.

Lastly, the African Union can help strengthen leadership and governance across member states by promoting accountability, integrity, and self-reliance. Through stronger peer review mechanisms, leadership development programs, and enforcement of democratic standards, the AU can help cultivate visionary and ethical leaders who serve citizens rather than personal or external interests. By aligning governance reforms with its various economic initiatives, the AU empowers member states to move from dependence to dignity—anchoring Africa’s progress on capable leadership, sound governance, and collective selfdetermination.

h) Electoral Systems and Judicial reforms

Weak electoral systems lie at the heart of Africa’s governance challenges, often entrenching corruption, mediocrity, and public distrust. Strengthening electoral processes and judicial reforms is therefore essential to ending dependency and unlocking Africa’s true potential. Transparent, credible elections ensure that leadership is chosen on merit and accountability rather than patronage, while an independent judiciary guarantees that the rule of law—not political influence— prevails. Together, they create an environment where competence is rewarded, institutions function effectively, and citizens regain faith in governance. For young technocrats and reform-minded leaders, this stability and fairness become powerful incentives to step forward—knowing their ideas can triumph over money and manipulation. In essence, electoral integrity and judicial independence are the twin engines of Africa’s renewal: they restore trust, attract domestic and diaspora investment, and empower a new generation to lead Africa from dependency to dignity.

From Vision to Impact: What if We Do It All?

Imagine an Africa in which:

• The manufacturing sector contributes over 20% of GDP, creating tens of millions of mid-skilled jobs.

• Intra-African trade rises to 30–40% of total trade, and intra-regional value chains flourish in agriculture, mining, manufacturing and services.

• African sovereign wealth or investment funds total hundreds of billions of dollars reinvested locally, creating global-scale companies headquartered in Africa.

• Young Africans across the continent are empowered through research, technology, entrepreneurship and innovation hubs and funding, turning Africa into a net exporter of ideas, not only raw materials.

• Governance reforms enable parliaments, judiciaries and regulatory systems to function robustly, reducing leaks, improving fiscal discipline, directing investment and enabling inclusive prosperity.

• Africa’s market of 1.4 billion people becomes a base for African-led companies, African brands, African supply chains—less reliant on exportonly models and more resilient to external shocks.

To translate this vision into action, we must make decisive and coordinated choices across the continent.

Conclusion: A Call to Purpose

The future we seek will not be given — it must be claimed. Africa’s destiny will not be defined in the boardrooms of Washington, Beijing, or Brussels, but in the imagination, courage, and conviction of Africans themselves. Let this Forum not conclude with mere communiqués. Let it mark a commitment—a continental compass—to redefine our development from within. The next generation of Africans should inherit:

• A continent that no longer waits for opportunity but creates it.

• A continent that no longer negotiates from weakness but from strength.

• A continent that no longer measures progress by external validation, but by the empowerment and well-being of its people.

Africa’s story is still being written. Let this be the chapter where dependency ends and dignity begins. Let it be the chapter where we stop asking “What can the world do for Africa?” and begin declaring “What will Africa contribute to the world?”

This is not merely a call for reform—it is a call for a renaissance: an African renaissance rooted in confidence, capacity and collective will. We need the next generation of leaders, who have not experienced colonial rule and believe nothing is impossible . Let this be the generation that reclaims Africa’s narrative, redefines its partnerships, and rekindles its power — not for a select few, but for all Africans, and for a world that needs Africa’s wisdom, resources, and humanity more than ever.

Together, let us build an Africa that no longer waits to be invited to the global table—but one that confidently crafts its own, sets the agenda and defines the terms of engagement. For this is Africa’s moment—not to be courted, not to be overlooked, but to be counted among the shapers of the world’s future.

*Being the full text of the Keynote Address By Former President of the Nigerian Senate, Senator AbubakarBukolaSaraki, at the at the Democracy Union for Africa Forum, Nairobi, Kenya with the theme: Navigating Africa’s Strategic Position in a Multipolar World: Towards Equitable and Mutually Beneficial Partnerships

Leave a comment