Jess Castellote

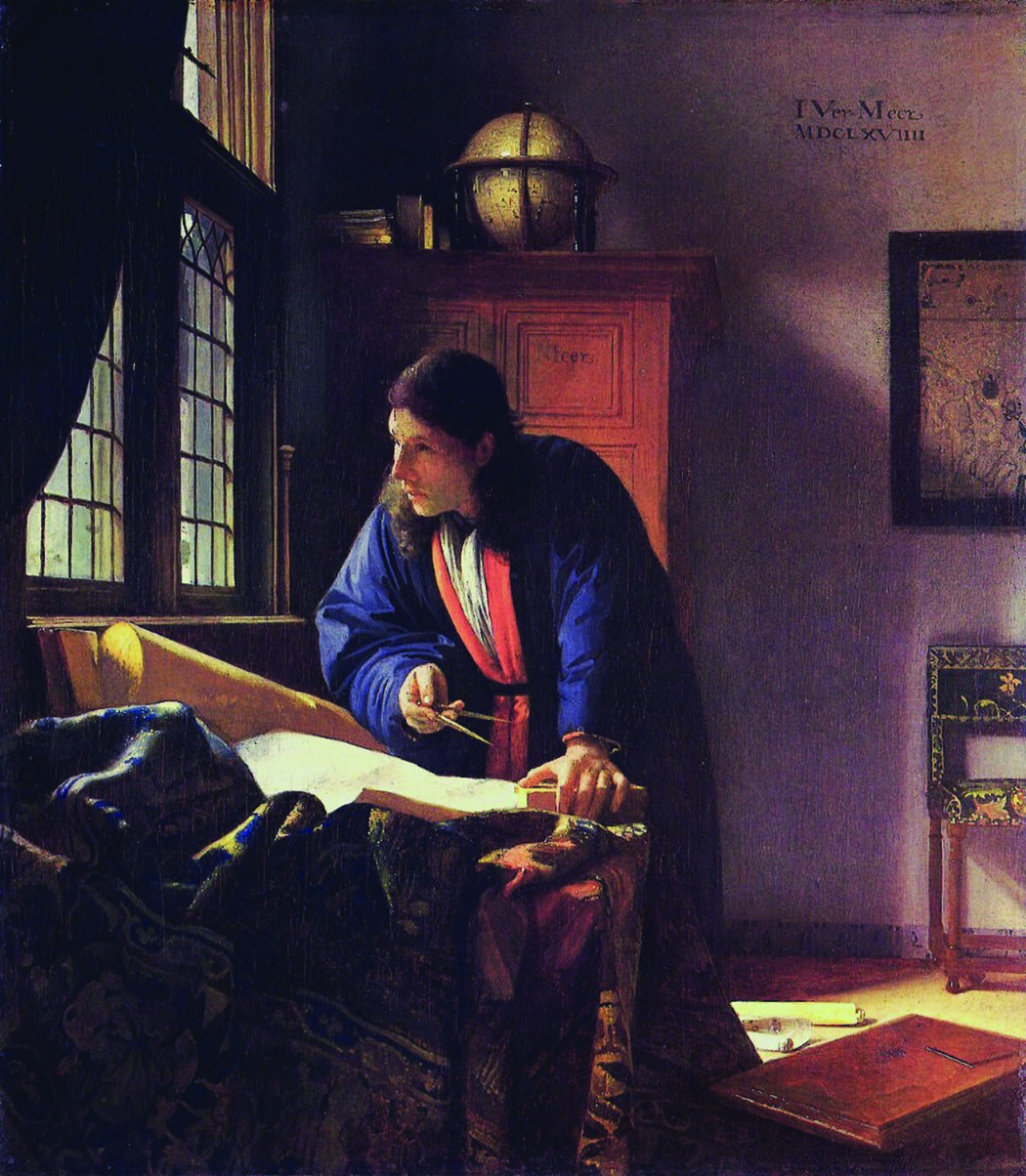

Last week I came across an article about Johannes Vermeer’s “The Geographer”, a wonderful work painted around 1669. It shows a scholar in his study, surrounded by maps, globes, and measuring instruments. The geographer has paused mid-work, turning toward the window, his posture tense with suspended discovery. Vermeer captures that moment just before insight strikes and the mind floats between confusion and clarity. You can almost feel the urge to sketch a new line and to revisit the map with fresh eyes. We don’t know what he sees or thinks, but we sense something has shifted. Vermeer catches him stepping beyond the material world into reflection, imagination, perhaps discovery.

When Vermeer painted this work 350 years ago, Dutch ships were active along the Gulf of Benin, pushing eastward from their West African trading posts. Though they never settled in what is now Nigeria, they traded regularly in the western Niger Delta, around the Benin River and the mangrove lands of the Itsekiris. I like to imagine Vermeer’s geographer tracing those unfamiliar Nigerian inlets and sandbars—pausing, as in the painting, just as a new line reveals a larger horizon. Or perhaps, in that moment, he was thinking beyond maps altogether, contemplating something far more important than coastlines and trade routes.

Looking closely at this painting made me think about how certain artworks help us look beyond. They stay with us not because of what they show, but because of what they reveal. They make us pause, look again, recognise that meaning often hides beneath the surface. Sometimes, they help us think about ourselves. The geographer’s gesture of looking beyond captures something basic about art’s power: it trains us to see more deeply, to look beyond surfaces, beyond appearances, beyond our own assumptions. In an age drowning in images and distractions, this is a valuable gift.

Ordinary life encourages rapid scanning over careful looking. Social media teaches scrolling, not thinking deeply. Advertisements flash past. Photographs vanish in seconds. But standing before a good painting demands a different rhythm. Our eyes begin moving with patience over colours, shapes, lines, textures. We notice relationships between light and shadow, and between what’s shown and what’s suggested. And sometimes, they invite us to stop and think about something altogether different. About something that is beyond what the artwork portraits.

In his book The Object Stares Back, the art historian James Elkins explains that looking is never as simple as it seems; when we slow down, images begin to reveal more than we first notice. I felt this while looking at Vermeer’s Geographer. At a quick glance, it seemed like nothing more than a man in a room with his maps and instruments. But when I looked at it more slowly, just as Elkins suggests, the painting began to “look back” at me. I noticed the pause in the man’s body, his hand resting on the table, and his powerful gaze turned toward the window instead of the tools before him. It felt as if he had stopped measuring the world and begun thinking about something larger, something that cannot be captured on a map, something that went beyond the present. His pause was a doorway where the mind steps beyond maps into something larger. In that moment, it reminded me of what Elkins means: real looking is not just seeing what is there but sensing what lies beyond it.

That gesture of looking beyond is not only his; it becomes an invitation. Just as the geographer looks past the room containing him, great artworks invite us beyond the canvas, into deeper ways of thought and possibility. In a world shaped by haste, art becomes a training ground for learning to see and learning to reflect.

Artists often use the visible world to point toward what lies beyond what we can see. What matters most is frequently what is implied rather than literally shown. Art becomes a doorway to the unseen, a space where absence and presence mix together. Looking beyond means perceiving connections between the painted and unpainted, form and feeling, reality depicted and ideas suggested. Good art expresses longing, memory, transcendence, fear, mystery, and much more. These are realities that resist straightforward description. In an era ruled by information and data, art reminds us that the world is larger than what we can measure. Art also challenges our assumptions. We think seeing is neutral, but we actually see through filters shaped by experience and culture. Art can shake up these filters, reveal their limits. It teaches humility—that our first interpretation may not be the whole story.

Another side of looking beyond comes from art’s ability to create empathy. Seeing beyond what we initially notice often means seeing into another person’s experience. A portrait confronts us with someone’s gaze and vulnerability. A narrative painting places us inside a story. A contemporary installation can draw us in the emotional world of migration, inequality, environmental destruction. This is not merely intellectual—it’s deeply emotional. These works invite us to expand our emotional horizons and look beyond our comfort zones. Art also helps us see what we don’t yet fully understand. Today’s artists grapple with identity, ecological crisis, artificial intelligence, global migration. Engaging with their work requires looking beyond the present moment into developing realities.

Perhaps the deepest shift occurs when art teaches us to look beyond ourselves. Encountering a work becomes a mirror reflecting our inner life. Some works invite looking inward; others unsettle us, raising questions we did not know we needed to ask ourselves. Through this process, we expand inwardly. Returning to Vermeer’s geographer, we sense that as he looks out of the window, he confronts not only the world but also himself. He stands at the edge between known and unknown, between certainty and inquiry. When we stand before such a painting, we are invited to consider our own boundaries. What are we overlooking? What assumptions shape our thinking? What is missing in my life? What might we discover if we paused and looked more attentively?

Looking beyond becomes more than an aesthetic exercise—it becomes a way of engaging with life. In a world of superficial impressions, quick judgements, and polarised opinions, the ability to see beneath surfaces is vital. It helps us interpret complexity, resist manipulation, appreciate nuance, cultivate empathy, imagine alternatives. Art remains one of the last spaces encouraging deep seeing without distraction or pressure. It trains the mind to stay attentive, the heart to remain open, the imagination to stay alive.

I have never been to the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, where The Geographer hangs, but I can imagine standing before it, learning and asking myself questions. The artwork guides our gaze, just as the geographer moves from window to map, from page to globe, from thought to experiment. It teaches us to value careful observation over rushing to conclusions. We become students rather than spectators. Vermeer invites us to watch, but also to think. It reminds us that understanding requires a willingness to see what lies beyond the edges of the map. What is out there, on the other side of the window.

This is what art cultivates in us. To look at art is to learn to look beyond: beyond the obvious, beyond the expected, beyond what we already know. We free ourselves from the limits of the familiar. Learning to look beyond in art helps us look beyond in life. And perhaps—like Vermeer’s geographer—we discover that the moment we truly begin to see is the moment we allow the light to enter. Great works take us out of the logic of calculation and productivity. Like in The Geographer, we must start by looking up and allowing the light filtering through a window to open unexpected horizons. This intense emotion before an artwork comes unforeseen, unplanned. It goes beyond monetary value or social media popularity. It is far deeper, more personal. The Geographer touches us because it highlights the value of attention. This serene scene convinces me: I must find a way to Frankfurt, to the Städel Museum, to spend a long time in front of this painting.

•Dr. Castellote is the director, Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, Pan-Atlantic University

Leave a comment