Sunday Ehigiator

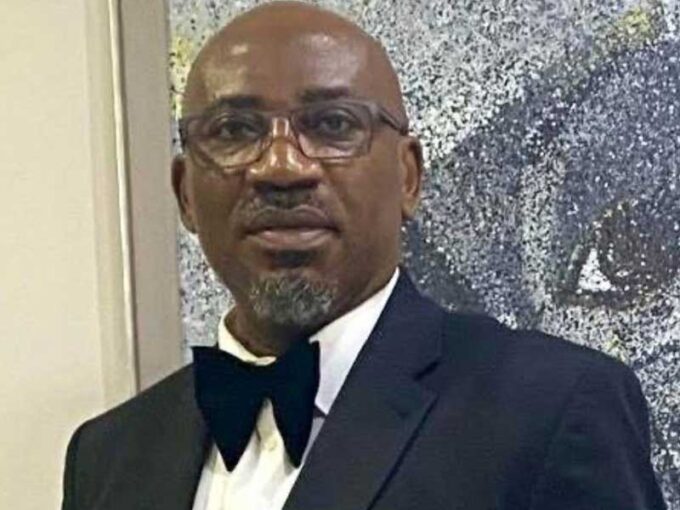

Not all men born of the soil walk with the hush of royalty. Fewer still leave behind a trail so luminous, it sings. Abdulsamad Rabiu, at 65, is one such man, less a tycoon, more a quiet cartographer of fortunes, laying down the railroads of Nigeria’s industrial renaissance with the calm of a sage and the grace of a patriarch who sees farther than most.

The Big Kahuna: Triumphs of Abdulsamad Rabiu at 65 is both a commemorative book and cultural artefact. A literary sculpture. A long, glinting river of prose, archiving in gilded ink the labours, values, and triumphs of a man who has given more than he has ever taken from his country.

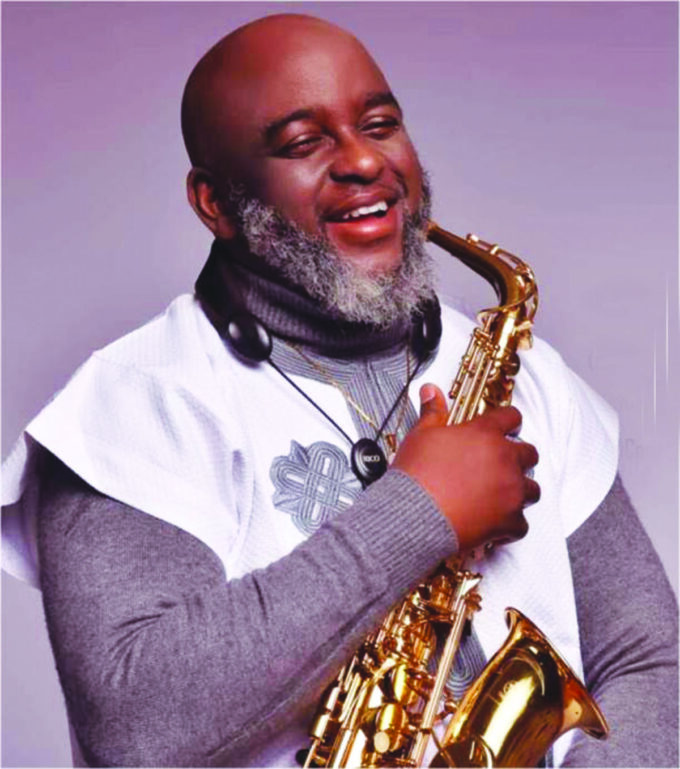

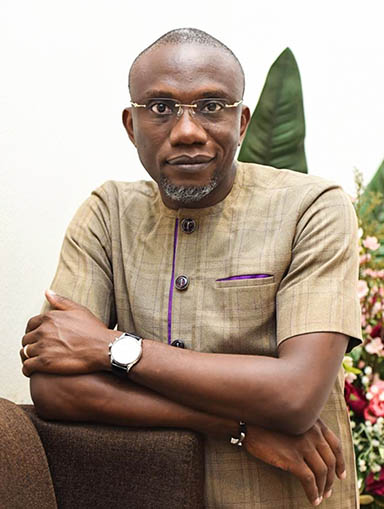

Penned by renowned prose stylist and biographer, Dr. Lanre Alfred, the book is a richly layered literary masterpiece of the Chairman of BUA Group, Abdulsamad Rabiu. The release of the book marks a heartfelt tribute to the magnate’s 65th birthday, which held on August 4, 2025.

Alfred, often hailed as the “Doctor of Letters” for his lyrical style and meticulous documentation of contemporary Nigerian history, has once again delivered a compelling account of leadership and entrepreneurship.

This new title, which stands as his ninth book, joins a distinguished collection of works such as ‘The Man Who Carried a City,” a richly layered 60th birthday special publication on Lagos State Governor, Mr. Babajide Olusola Sanwo-Olu, Titans…The Amazing Exploits of Nigeria’s Greatest Achievers, Pacemaker – Triumphs of Igho Sanomi at 40, and Dapo Abiodun: The State House As His Pulpit, among others.

The Big Kahuna becomes necessary, argued Alfred, not just because Rabiu has turned 65, but because rarely do we find in our national story a man who has lived so generously without fanfare, who has built so monumentally without ever needing the world to applaud. He is a study in balance: between wealth and wisdom, legacy and humility, commerce and conscience. At a time when Nigeria teeters between chaos and potential, Rabiu’s life becomes the very compass we need, a living testimony that prosperity can be built without plunder, that success can be quiet, dignified, and communal.

The book opens with a Prologue that doesn’t merely set the tone, it casts a spell. Here, the reader is drawn into the allegorical depths of Rabiu’s essence: not as a billionaire in the conventional sense, but as a custodian of values, a steward of fortune tasked with nurturing not only the empire of BUA, but the dreams of a continent. It offers an invitation into a narrative woven with silk and steel, where the vocabulary of legacy is not shouted, but whispered through deeds and decades of devotion.

The first chapter, Born with the Flag, steps back into the soil from which Rabiu sprouted. It chronicles his origin in Kano, a city both ancient and bustling with trade, showing how the son of Khalifah Rabiu was destined to inherit both enterprise and empathy. It draws a vivid portrait of a childhood where the values of hard work, humility, and cultural rootedness were instilled like sacred hymns. Rabiu is shown not as a product of luck but of lineage and labour, a man born not just into wealth, but into responsibility.

The Quiet Tycoon, the next chapter, strips away the noise that usually follows billionaires. It is here that the reader encounters the soul of the man, an entrepreneur whose genius is eclipsed only by his gentleness. Rabiu’s rise through the industrial ladders is not recounted as a conquest, but as an offering; each milestone achieved not for self-glorification, but for national elevation. He is cast in stark contrast to the brash, performative elite of today. Here is a man who built BUA into one of Africa’s most respected conglomerates without ever demanding a spotlight.

Then comes Empire in Motion, a panoramic sweep of Rabiu’s industries, the flour mills, the cement factories, the sugar refineries, the ports and pipelines. But it isn’t just a ledger of assets; it is an ode to vision. The chapter illustrates how Rabiu moves not just money, but meaning. It celebrates his foresight in backward integration, his insistence on local production, his employment of thousands, ordinary Nigerians whose lives are elevated because one man dared to build.

This dovetails into The Power in the Pipes, where Rabiu’s infrastructural audacity is laid bare. His ports. His pipelines. His refinery dreams. Each project becomes an artery through which Nigeria’s industrial future might beat. In a nation where infrastructural decay has become scripture, Rabiu’s vision is revolutionary, less about profit, more about providence.

The Green Gospel of Self-Sufficiency is perhaps the most didactic of the chapters, celebrating Rabiu’s intervention in agriculture, not as a billionaire’s CSR project, but as a patriotic crusade. It narrates how he has plowed his wealth into rice, sugar, and flour production not merely to turn a profit, but to feed a nation. The reader is reminded that food is sovereignty, and that Rabiu’s quest for self-sufficiency is one of the most selfless acts of nation-building in modern Africa.

, Markets and Morality asks an uncomfortable question: Can capitalism be kind? In Rabiu’s world, the answer is yes. This chapter explores the moral scaffolding of his business decisions, such as his groundbreaking move to crash the price of rice at a time when inflation gnawed at the entrails of the nation. The billionaire is not presented here as a saviour, but as a steward, one who knows that the truest profit is dignity restored.

Torchbearer’s Salute: When Rabiu Hailed Tinubu offers a politically textured portrait. It recounts how Rabiu, a man known for his reticence in politics, broke protocol to endorse President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s economic reforms. His praise was not partisan, but principled, an act rooted in shared vision. The chapter becomes a subtle meditation on leadership and alignment, showing that sometimes, a country’s turnaround requires not just a great president, but great patriots willing to affirm what is right.

From there, the book veers into the realm of philanthropy with The Samaritan Blueprint: A Titan’s Philanthropic Labours. It is an emotive chronicle of Rabiu’s interventions in healthcare, education, security, and infrastructure through the ASR Africa initiative. But what stands out is not just the quantum of his giving, but the discretion with which he gives. Rabiu’s style of philanthropy: silent, strategic, and widespread, contrasts the noisy performativity of others. He builds hospitals without press conferences, donates billions without hashtags. In a world obsessed with optics, his is a refreshing gospel of quiet impact.

Then comes The Global Citizen, which traces his influence beyond Nigeria’s borders. Here, Rabiu is framed not just as an industrialist, but as a statesman without a title, one whose cross-border partnerships, global diplomacy, and international presence make him one of Africa’s most respected private citizens. The chapter paints Rabiu as a man fluent in both the boardroom and the banquet hall of international affairs, proving that soft power need not shout to be heard.

But perhaps the most poignant of all is Letters to the Future. This chapter is constructed as a philosophical archive, distilling the man’s thoughts into twenty-six meditative quotes, one for each letter of the alphabet. Each quote is paired with context, showing the moral, spiritual, or entrepreneurial soil from which it sprouted. In this chapter, Rabiu becomes a teacher, a mentor from afar, offering young Africans a manual for living, leading, and lasting. It is not mere quote-peddling; it is legacy engraving.

The final chapter, The Quintessential Father, is a moving meditation on Rabiu’s fatherhood. Inspired by the billionaire’s rare public appearance at his son Khalifa’s graduation at Georgetown University, it demolishes the tired stereotype of the absentee rich dad. Rabiu, it argues, is that rare tycoon who shows up, not just in boardrooms, but in bedrooms, school halls, and vacation dinners. The chapter exalts fatherhood not as duty but as devotion, showing how Rabiu’s greatest legacy may not be his empire, but the character of his children, polite, dignified, unseen, yet deeply rooted.

Then comes the Epilogue, which does not close the book so much as open the reader’s eyes. It circles back to the metaphor of the fortunemaker, not just as one who makes wealth, but one who bestows fortune: to his family, to his country, to his time. Rabiu, it concludes, is not just a man of his age, but a man for all ages, a lighthouse, not just for Nigeria, but for the African dream.

Why, then, is this book necessary?

Because Rabiu is a mirror in which the best of Nigeria might see itself. Because the story of Nigeria must not be written only in blood and corruption, but in the ink of builders and givers. Because our children must know that greatness does not always roar, it sometimes whispers. And because in celebrating Rabiu, we are not elevating a man; we are enshrining a philosophy: that wealth must serve, that dignity can prosper, that silence can thunder, and that to make a fortune is to be entrusted with the sacred task of fortifying others.

The Big Kahuna is thus a bridge between history and hope, between commerce and conscience, between one man’s triumphs and a nation’s possibilities. Through its pages, Abdulsamad Rabiu stands immortal, not because he asked for it, but because he earned it. And through its words, the reader is reminded that even in a land riddled with noise and failure, a quiet legacy can still rise, glorious and evergreen.

This book, ornately penned by Dr. Alfredresonates as a national gratitude in literary form. It reasserts the value of honouring our builders while they are still among us. In celebrating Rabiu, we are reminded that wealth is not the final word, what you do with it, and how it reshapes the world around you, is what counts.

At 65, Abdulsamad Rabiu remains a paradox: titan and teacher, empire-builder and silent giver, boardroom strategist and barefoot philanthropist. And this book, crafted with elegance and editorial integrity, gives him the tribute he never asked for but so deeply deserves.

Leave a comment