Your Ticket Out of Poverty

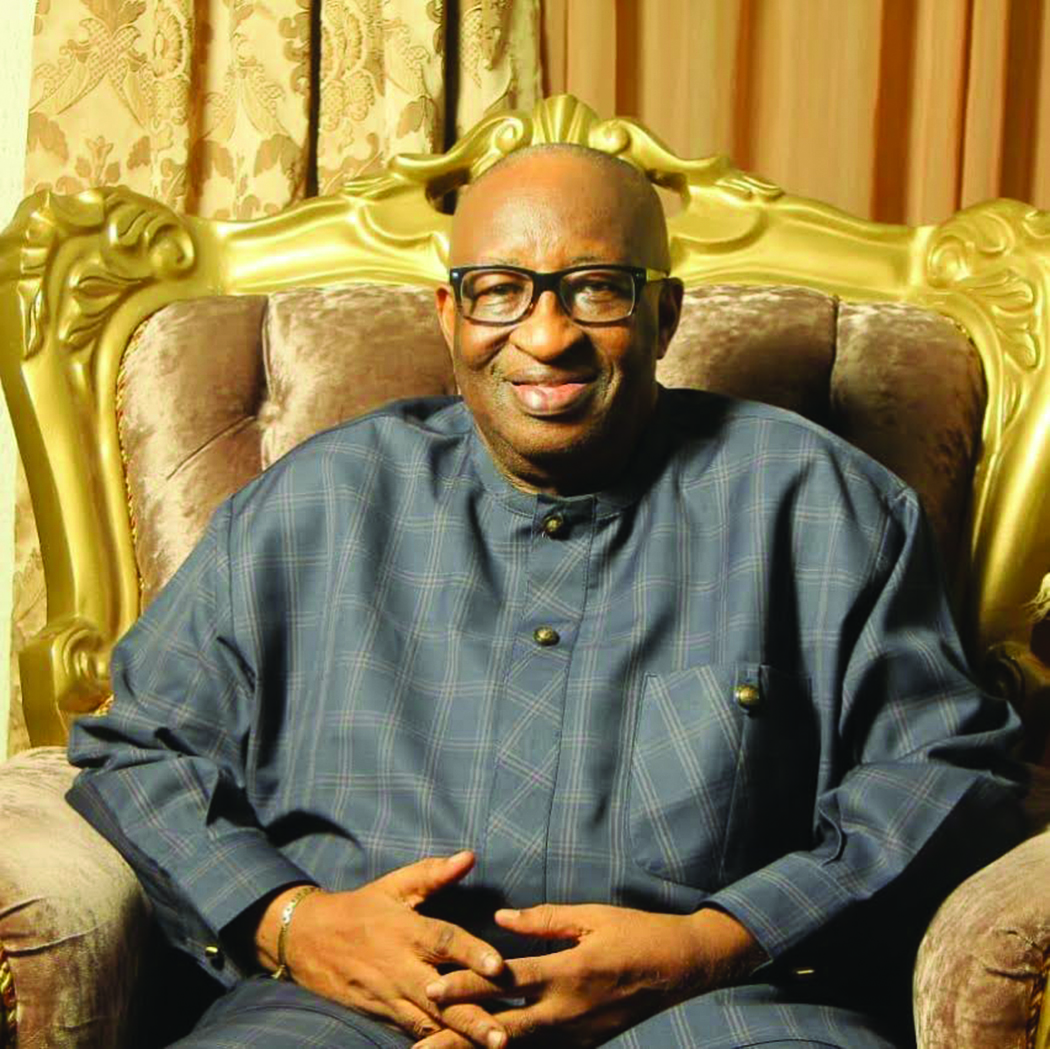

The life of Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Uyo, and former Director General of West African Institute for Financial and Economic Management, Prof. Akpan Hogan Ekpo, reads like a blend of grit, curiosity, and purpose, shaped by a childhood in Lagos police barracks, early exposure to social inequalities, and a relentless quest for knowledge. From marching with sticks as “guns” alongside childhood friends to wondering why some classmates could afford lunch while others couldn’t, his formative years planted deep questions about class, justice, and the structure of society.

Those questions trailed him through his education, first in public schools alongside children of ministers, later in the United States at Howard University, where his worldview was sharpened by radical ideas, African literature, and the life of struggles of African Americans. His journey took him from clerking at the Nigerian Ports Authority to earning two Ph.Ds, holding key policy roles, and sanitising the University of Uyo as vice chancellor. In this conversation, the respected economist and former Director General of the West African Institute for Financial and Economic Management reflects on his defining moments in public service, the principles that shaped his decisions, among others. Dike Onwuamaeze presents the excerpts:

Growing up as the son of a police officer in Lagos, what are the fondest memories of your childhood?

There are lot of them. But the one we used to enjoy most at the barracks as little kids was that we wanted to behave like our parents. So, we will organise ourselves and be marching like our parents on parade with sticks for guns. The other fun was that when I started primary school at St. Paul, Ebute Metta, we will stop to play soccer before getting to the school and we will arrive late at school. Apart from canning us, my teachers would tell my parents, and my mother would follow me to school and sit at the corridor to make sure that I do not go and play soccer again. Today, children go to nursery school. During our time, there was no nursery school, but what they called lesson. They will pack us in one area of the barracks to teach us A, B, C, D. My parents gave me a slate as my writing board, but I was not enjoying the lessons. So, I dropped the slate and it scattered on the floor and I was so happy that there would be no more lessons. But they bought me another slate made from a plank and when I dropped it on the floor, it did not crack, which meant no escape from going to school.

How did your early life in Lagos and the barracks shape your worldview and academic curiosity?

I started primary school at St. Paul, Ebute Metta, in Lagos State. Later my father was transferred to a police barrack in Marine Beach, and I moved to a school called Anglican Isoko Primary School, Marine Beach. Some of us will trek to school, and others would be dropped with vehicles. I started wondering how come my dad does not have a car to drop me. Also, when it is time for launch, some kids will have money to buy food, and others could not. But what I want to stress is that the children of both the rich and the poor mixed together in schools. There was only one private school then in Lagos, which was Corona School, and all other schools were public faith-based. Then the ministers’ children went to public school in those days. That shaped my thinking about groups and classes. Why do some have and others do not have? Interestingly enough, when I wanted to go to secondary school, I could not make it to Kings College. By this time, we were living at 38 Kirikiri Road, Apapa Ajegunle, and there was a school around there called United Christians Secondary School. My father checked the school and found out that it has white principal and European teachers. The school was owned by three missions, namely the Anglicans, Baptists and Methodists. Then I was very curious about social and political events. I was reading a newspaper and saw an advertisement that a “house boy is wanted and he must be an Ibibio.” So, I started being curious about how a society is shaped. Then, as we trekked to go to school, I would see that people were living in the European Quarters, which is now called GRA and I started thinking about classes in the society. This was shaping my thinking about society. Then, in my secondary school, there was an abstract titled “The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah” in a textbook we used for English Language comprehension. I read the abstract and it had a strong influence on me. But luckily for us the school system was not segmented. So, some kids living in the GRA were our classmates. I studied English and French with language laboratories. I saw that lab again in Howard University when I went to do my first degree and you must do a foreign language. The training in secondary school and the lives some of us lived influenced me. My dad retired not rich and with dependents, that he told us that nobody will go further in education after secondary school because he could not sponsor our education beyond secondary school. Because of that, our training from our parents was stunted in a way. Part of that hardship shaped my thinking about society and how I can contribute to make better for those who are downtrodden. While waiting for my results after finishing secondary school, I got a job with the Nigerian Ports Authority (NPA), as a clerk through one of my dad’s friends, Mr. Henshaw. At NPA I started taking interest in trade union activities. I also saw that those working overtime were still having difficulty living well. I refused doing overtime, because I was studying for my A’Levels on my own. I went to St. Pauls, where the University of Ibadan was doing extra moral studies and paid to get evidence that I am in school, which would allow me to leave by 12 noon. This gave me the opportunity to visit the National Library to read every afternoon. My experience at NPA also shaped my life, and I decided that in life, if I make it, I will always try to make life better for the downtrodden. While I was in the NPA, the federal government advertised for scholarship for tertiary institutions. I applied and got the scholarship and intended to study in America. But my father refused insisting that I should attend the University of Lagos because people abroad suffer a lot. But a lecturer in Unilag who came from our area, Mr. I. Ukpong, an economist who studied in the United States, advised my father to allow me to go to America. So, I left for the United States.

What was it like leaving Nigeria as a young man in the 1970s to study in the United States of America?

I had no plan to go to the United States for studies. My plan was to study in Nigeria, but the circumstances that I have explained above led to my going to the United States. But when it came that I had to go to the United States, it was a little bit emotional. My mother gave me her scarf and said that I should bring it back when returning. After I had boarded the airline, my uncle came into the airline to bid me farewell and give me his last bit of advice: ‘As you go to study in the United States, please do not marry a white woman. But if you find one that can give everyone in the village a job, you can marry her.” When I arrived in New York, my friend was waiting to receive me. As I was seated waiting, my mind told me that I will come back to Nigeria once I finished my studies. I enrolled in Howard University as an undergraduate. Historically, Howard University is a black American university and I learnt a lot from the university. It has a library with the largest collection of black authors’ books in the world. That is where I read about Nigeria. In fact, I became an African in Howard University. I read books written by Mbonu Ejike. I spent time reading. Howard University radicalised my thinking. I saw the oppression of African Americans and I equated it with what we were going through in Nigeria and that started raising my consciousness.

You were on the dean’s list throughout your studies. What motivated that excellence in you?

Hard work! I decide that to liberate Nigeria or Africa, I must first liberate myself. So I dedicated myself to studying hard to acquire knowledge and earn a university degree to conquer poverty that I come from. In our days in Nigeria, a first degree meant that you have left poverty behind you. But the funny thing is that when I got the letter that I am on the dean’s list and went for the ceremony, unknown to me, the parents and relations of the African Americans that were on the dean’s list came for the ceremony and took pictures with them and I was a loner. I called my cousin and others that I had informed about the ceremony and they told me that they were working. And that was the last time that I attended the ceremony. I was invited every year but I did not attend anymore. I worked hard as a student to fast track my going back to Nigeria. So, I took courses in neighbouring schools, which the university system in America allowed. But nobody advised me that those outside courses would not carry their full credits when transferred to my university. So, I missed first class grade by .03. I finished in three years instead of four. And because of my G.P.A Howard University gave me scholarship. That is why I cannot forget Howard University.

What was the major culture shock you experienced while staying in the United States?

I did not have much culture shock in the sense that I read a lot of Kwame Nkrumah’s book that detailed his experiences in America. But my shock in America was in the area of food. Another shock that I had was seeing two men kissing properly.

How did you manage to pursue two Ph.D degrees and what kept you going during those intense academic periods?

When I left Howard University I went to University of Pittsburg to do my Ph.D. I did not want to do everything in one school. In the north east America, Economics was in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and not in the school of business. But we can take courses in the Faculty of Business. At Pittsburg University I was being sponsored by the University of Calabar’s staff development. Unical came to recruit people in America and I went for that interview. I was the first to be hired without teaching one day in Calabar. The University of Calabar was paying my fees in Pittsburg. But some of my courses in Economics were in the business school and when I went to combine my credits the university said that they were different programs and that I must pay the fees for the Faculty of Business. My colleague told me about a distance learning university in California so I transferred all the credits in the courses I did in business to California Western. So I earned Ph.D in Economics from Pittsburg and Ph.D in Business Administration from California Western.

You have worked with top financial institutions like WAIFEM, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Ministry of Finance, IMF and others. What moment stands out most defining in your public policy journey?

Actually, I did not work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as a staff. But, I was a visiting scholar at different times. I got linked to the IMF in two ways. In the late 1980s there was crisis in the Nigerian university system and lecturers were leaving in what was called the brain drain. I left for Zimbabwe in 1989. I worked for about three years in Zimbabwe where I was exposed to the IMF and the World Bank. There was a consortium called ARC. I got involved with them because they were funding research with what is called in-built-salary to keep African economists in Africa to influence policies rather than going abroad. But the most defining for me was my engagement with the Federal Ministry of Finance in the 1990s when I was the chairman of the Ministerial Advisory Committee. It gave me exposure to the inner workings of the government. People do not know that I have been a member of every economic management team either directly or indirectly, except the present administration. The other one was when I was the vice chancellor in the University of Uyo for five years. It was defining because in my own little way I was able to implement some of my principles that university is not for everybody and you do not have to fake credentials to get in. By the end of my tenure I sent away over 2,000 students who entered illegally or were involved in cultism. In fact they called me “sanitiser.” I sanitised the University of Uyo in that period. I busted the syndicate of someone that was printing fake certificates of our university for over 13 years. It was a joy that I was able to return the university to what it should be. I rescreened every student because I had a situation where somebody had a first class but could not write good English. It was a defining moment.

Your wife is a Kenyan. How did you meet her?

We met in the university in the United States. It is 48 years of marriage now. She is an activist. Apart from being a woman with beautiful character, her activism was important because when I was being chased around in Nigeria by the police and the State Security Service (SSS) she understood what we were going through. I spent one year in the University of Abuja but I was sacked and detained because of forming the Academic Staff Union of University (ASUU). Cultural shock is not there because you will be amazed that Africa is almost the same. For example, I first saw a village in Kenya and not in Nigeria because I went to her village to marry her.

How do you stay grounded in your personal life in spite of your travels?

I do a lot of community work. At my spare time I look at what Nigerian government is doing and see how I can contribute to let them do the right thing. And I read a lot outside of Economics. I also take part in church activities. Presently, I am blessed with about 10 grandchildren.

What role has faith played in your life’s journey as an academic and in your personal life?

Faith played a major role in my early life as a teenager. I was part of the Scripture Union. My late dad was a very senior elder in Qua Iboe Church and I was very active in the church. But you will be disappointed that I went to the United States with the zeal of a born again Christian but I lost interest in the church for several reasons. I saw a clear racism. I remembered that I went to a church somewhere in Virginia and sat down and all the white people left me. I also went for the Holy Communion in another church and in those days you we have to line up. You take the bread and the wine and pass it on to the next person. But I did mine and nobody took the cup from me. I wrote to my father that this Christianity the white men brought to us that I am in their country and seeing racism and discrimination. He replied me quoting the scriptures. I then decided that I cannot say that there is no God but I will not be part of what they were practicing in the United States. So, I wanted to be a Marxist Christian, but non-denominational. I studied the life of Jesus Christ and saw that there was 90 per cent socialism in Jesus Christ. That was why I told my wife that I would not marry her in church in the United States because I do not believe that they were honest. When I came back to Nigeria we went to bless our marriage in the church in Lagos in order not to bring my father down because he was a senior member of the Qua Iboe Church. Faith is important and I am not an atheist.

If you will go back in time and give young Akpan Hogan Ekpo an advice, what will it be?

Hard work! Hard work! Hard work! Always help your fellow human beings. Have faith and believe in God and whatever you want to be, be the best.

What does a typical day look like for you now that you have retired?

I no longer rush out of the bed as I used to do. In those days I will write until 5 a.m. and leave from my study to the airport. But that has stopped and if someone call me by 10 a.m. I will not pick up the call until 11a.m. because my phone is on silent. I still go to the office and co-teach a course with one of my former students who is now a professor. I mentor students and supervise postgraduate students. I am active with the Nigerian Economist Society, of which I was a former chairman. I do things in moderation now because my body cannot take certain things anymore.

What is your advice to Nigeria’s current economic managers on how to leapfrog growth, address poverty, inequality and other economic challenges?

The current economic managers should put Nigerians first. For me, in their first two years, they were not doing that. In economics, you can forecast what will happen going forward. By my own observation, only 10 per cent of Nigerians today are living a normal life. The political class, elites, CEOs, are living a normal life but the rest are not. In economics, there are policies that you put in place and if after a year, you are not getting some results, you re-examine them. Economics, though an inexact science, is a science of alternatives and there are several ways of being a capitalist. But you do not encourage primitive accumulation of wealth at the expense of the people. What drives capitalist development is the middle class. Once they are not there, it is just a few at the top and the rest at the bottom. In every country, those who are rich are very few, but those who are living comfortably are many and determine who will govern them. But when they are no more or they are frustrated, you will have chaos. The policies the government has in place were either not properly thought out or are motivated by self-interest. There are people that do not take development serious because they are benefiting from underdevelopment. Every country carries out reforms. For instance, the type of reforms Nigeria does all the time is called neoliberal reforms where one person will benefit and the other eight will suffer. President Bola Tinubu came into power and said “subsidy is gone.” He did not need to say that on that day because from July subsidy would no longer in the budget. Again, oil determines the structure of the Nigerian economy. You need to have consulted widely with experts to see how he could have removed it and still minimise the suffering of the people. We know that subsidy is a scam because we have been subsidising the wrong side of the curve. We were subsidising the supply side while the demand side was all a scam. The government should have removed it in phases because every country in the world has subsidy. Even the food IMF’s staff eat in their canteen is heavily subsidised. The “subsidy is gone” approach cannot help the people. I can tell you that all the countries that have leapfrogged and grown fast and have developed did not implement liberal economic policies, which is the trickle-down effect that if a few grow it will trickle down to the rest. Growth is not development, though it is a necessary condition for development. So, the policy is anti-people. Two-thirds of Nigerians are in multidimensional poverty. The middle class and intellectuals are now poor. Then the next thing is the exchange rate. I am shocked that some of my colleagues no longer understand the competitive market model, which is a benchmark for comparing other models. It is an ideal situation but there are conditions for it. The foreign exchange in our context cannot be competitive. We cannot determine the value of the Naira by using the market. First, the Naira is not convertible.

Second, our economy is not productive. Thirdly, we depend on sale of crude oil for foreign exchange. Look at the structure of the economy. The manufacturing sector is contributing less than three per cent of the GDP since 1963. The data is there. There are conditions for the market to determine the value of the Naira. There must be existence, uniqueness and stability. You cannot find that in practice. It is theory. So, in our context you do a managed float.

Let the central bank leave the FX market and we will see what will happen. The problem with Godwin Emefiele’s CBN was that it had too many exchange rates. When you have stability you have to ask at what price is that stability and in whose interest? Stability at N1,500 is not stability. And you must stay there for one year. Inflation is coming down because the economy was rebased. We all play this trick when we are doing research. In rebasing the CPI you look for what year that will favour you and pick that year as your base year. In 2024, the economy was still in a stagflation phase that means sluggish growth, high unemployment and rising prices. Then you put more items in your basket, it may be 700 and you ran the model. Of course the inflation rate will come down. But does it reflect prices in the market? No! So, it is artificial. Must they rebase the CPI? Our unemployment rate is a joke. It is not possible for it to drop from 33.3 to 5.1, which in a sane economy is full employment. You cannot say that I am employed if I work for two hours in a week. The ILO formula may be suitable in Europe. If you spend more than 10 per cent of your income on food, there is a problem. That is why I am saying that it can be reversed if they are serious. The cash transfer programme of N75,000 that is paid in three installments is a joke. It cannot help anybody. First is to be honest that the economy is not doing well. Then gather experts who will tell you how to proceed if you are honest. The president should reset the economy if he is serious.

Leave a comment