Ferdinand Ekechukwu

The atmosphere was radiant, the hall beautifully adorned, and the mood joyful. Guests arrived in colourful attire, reflecting the splendour of the occasion. It was immediately evident to all who attended that a great man was being honoured.

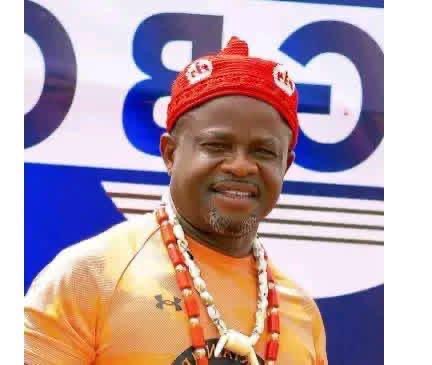

Such was the carnival-like ambience at the grand celebration of Prince Ademola Haastrup, a retired senior police officer, recently at Marcellina’s Place, Ikeja. The event brought together family, friends, former colleagues, and well-wishers in an outpouring of admiration and thanksgiving for a life of impact and purpose.

For many in attendance, it was a moment of reflection — a reminder of the blessing of longevity and the joy of being surrounded by a loving family that cherishes one’s legacy while still alive.

A Love That Has Endured the Test of Time

Leading the chorus of tributes was Princess Olufunke Haastrup, the celebrant’s devoted wife, who spoke with deep affection about their enduring bond. “I thank God for the love we have shared for 56 years,” she said. “Your dedication to our home and your unwavering faith in God reflect the good Christian that you are. You have always been a hardworking man and a generous giver — one who worked tirelessly to ensure the comfort and well-being of both your immediate and extended family.”

A Godly Father and Disciplinarian

Speaking on behalf of the children, Prince Adeniran Haastrup painted a heartfelt picture of his father’s strong moral compass and godly upbringing. “From when we were very young, daddy would say he didn’t care what we all did, but on Sundays, everyone must go to church,” he recalled. “He always said he didn’t know how to visit the house of any oracle or idol — he only knew how to serve God, who never failed his parents, and who has never failed him. He made sure to pass that faith and discipline on to us.”

Adeniran also spoke about his father’s exceptional work ethic and dedication to duty. “Even when he was granted leave, he rarely took vacations. He would always find a reason to work or to help someone. His senior officers respected his judgment, focus, and integrity. He was always given the toughest assignments — and though it often kept him away from home, it taught us the value of hard work.”

A Sacrificial Spirit

According to Adeniran, perhaps the most striking quality of Prince Haastrup is his selflessness. “Daddy would always say he didn’t care if he went hungry, as long as his children — and even others — had food to eat and a roof over their heads. When his elder brother passed in his 50s, Daddy took full responsibility for his children too. He has seamlessly played the roles of disciplinarian, father figure, mentor, and adviser.”

He further expressed gratitude to God for fulfilling the prophecy of longevity over his father’s life. “Just as the Bible says that rain does not return to the sky without watering the earth, every word God has spoken about his life has been fulfilled. We always believed he would live to a ripe old age — and today, we celebrate that testimony.”

A Legacy of Love and Service

Echoing similar sentiments, Prince Adegbayi Haastrup, the celebrant’s second son, described his father as a man of generosity, guidance, and determination. “I once told him I wanted to attend the University of Lagos, and he did everything possible to make it happen. When I had issues with some friends, he was upset at first, but he handled the situation with wisdom. That’s who he is — always there for family, friends, and even strangers.”

Adegbayi fondly recalled his father’s gestures of love.

“When I was going to university, he gave me keys to two cars — a Volkswagen and a Mercedes. They weren’t flashy, but they were meaningful. That’s how he shows care — through quiet, consistent sacrifice.” He also highlighted Prince Haastrup’s faith and community spirit. “He loves to pray and has even built churches — one in his community and another in the Ojodu Berger area — which he funds personally. That shows how much he loves God and how deeply he is committed to serving others.”

A Life of Grace and Greatness

As tributes flowed and laughter filled the hall, it was clear that Prince Ademola Haastrup had lived a life defined by faith, family, and service. His legacy stands not only in his career achievements but in the countless lives he has touched — through his generosity, discipline, and unwavering trust in God. At 80, he remains a beacon of inspiration — a reminder that greatness is measured not by wealth or titles, but by the love one gives, the values one upholds, and the lives one uplifts.

Leave a comment