When Amaechi Okobi walked into the Tate Modern in London, he did not expect to feel emotional. Standing before seven sculptures by Ben Enwonwu, he found himself overcome by pride, nostalgia, and a quiet sense of awe.

For years, those same sculptures, familiar to many Access Holdings employees, stood in the lobby of the company’s Lagos headquarters.

Staff encountered them daily, sometimes pausing to take them in, often simply moving past on their way to meetings or errands. But here, beneath the precision lighting and reverent silence of one of the world’s foremost museums, they appeared transformed.

“They were beautiful,” Amaechi recalled. “For years, they stood quietly in our building. But here they were, bathed in light, surrounded by awe. It was as if I was seeing them for the first time.”

The sculptures, on loan from Access Holdings, are part of Nigerian Modernism, a landmark exhibition at Tate Modern celebrating Nigeria’s post-independence artistic renaissance from the 1940s to the 1970s, an era when Nigerian artists asserted their own voice, blending global influences with distinctly African expression.

For Amaechi, who is the Chief Communications Officer at Access Holdings, the moment was more than aesthetic appreciation. It was an affirmation of identity, history, and presence.

“This was not just art on display,” he said quietly. “It was us, seen, celebrated, and appreciated.”

From Lagos to London: A Story of Preservation

The seven Enwonwu sculptures, once fixtures at Access Holdings’ headquarters, now command global attention at Tate Modern. Their journey from a corporate lobby in Lagos to the halls of an international museum is more than logistical, it is an act of cultural preservation.

“Loaning them to this exhibition was not just an act of generosity. It was an act of preservation,” Amaechi explained. “It ensured that Nigeria’s story, told through Enwonwu’s genius, reached the world.”

He has a point. Many African artworks disappear into private collections, inaccessible to the public and scholars. By opening its collection, Access Holdings not only safeguarded the works but restored their visibility, ensuring they continue to illuminate Nigeria’s creative legacy.

“Had they been acquired by others, these sculptures might have vanished into obscurity,” he added. “Instead, they now stand as ambassadors of Nigerian creativity, reminding the world of our enduring brilliance.”

Culture, Knowledge, and Capital in Harmony

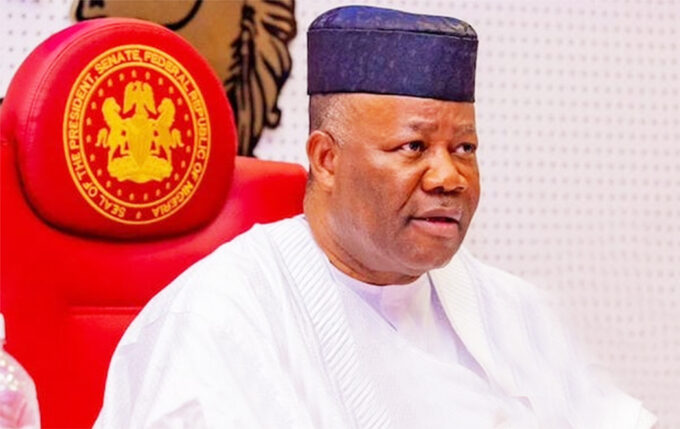

This moment reflects a broader philosophy within Access Holdings, championed by Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede CFR, its chairman, that national wealth thrives where culture, knowledge, and capital intersect.

“This exhibition is a perfect expression of that belief,” Amaechi noted. “Financial capital allowed us to acquire and preserve these sculptures. Knowledge helped us recognise their importance. And culture gives them meaning, connecting them to the people and nation they represent.”

By supporting Nigerian Modernism, Access demonstrates how corporate institutions can shape global conversations about African creativity, identity, and heritage.

Beyond Finance: Culture as Brand Strategy

For a financial powerhouse like Access Holdings, investing in culture may seem unconventional. But for Amaechi, it is entirely consistent with the company’s purpose.

“Culture humanises finance,” he said. “It tells the world who we are, what we value, and why we exist beyond profit.”

Through its enduring support for art, music, literature, and social impact initiatives, Access has built a brand identity that transcends traditional banking, one that celebrates African excellence and connects emotionally with its stakeholders.

“When people see Access investing in art and culture, they see a brand investing in them and their future,” Amaechi reflected. “That emotional connection is something money alone can’t buy.”

A Global Stage for African Stories

Seeing Nigerian art celebrated at the heart of global modernism carries both symbolic and strategic weight. For Access, this is cultural diplomacy, an act of shaping how Africa’s story is told and understood.

“It is surreal,” Amaechi said. “Those sculptures carry our pride and our brilliance. Seeing them here proves what we have always believed: that Africa’s excellence belongs anywhere in the world.”

This act of sharing reflects Access Holdings’ broader philosophy: to enrich Africa not only economically, but culturally and intellectually.

“When brands like Access champion culture, we do not just fund exhibitions, we shape how the world sees Africa,” he said. “We remind everyone that Africa is not emerging, it has always been.”

Leadership, Storytelling, and the Power of Culture

As visitors moved through the galleries at Tate Modern, Amaechi lingered before the sculptures, contemplating not only his role as a communicator but as a storyteller and leader.

“Leadership is not only about performance; it is about preserving meaning,” he said. “Facts may inform, but stories inspire. What we did here was not just about displaying art; it was about telling a story of identity and the partnership between business and culture.”

That is what made the moment so emotional. Beyond marble and bronze, beyond the curated space, this exhibition symbolises something larger: a generation of Africans reclaiming their narrative and institutions like Access helping to make that narrative visible.

In Amaechi’s words, “Culture dissolves borders. It invites empathy, curiosity, and connection.”

If he had to summarise the experience in a single word, he does not hesitate. “Emotional,” he says again, smiling.

Leave a comment